I am one of those “trying to recover from their childhoods” of the nineteen seventies and eighties of Nepal.

To a casual observer, whether local or foreign, Nepal was a peaceful, non-violent country then (and still is).

We are, after all, the country where Siddhartha Gautam, the historical Buddha who championed the Principle of Non-violence (Ahimsa), was born. That must, in some way, show in us, surely!

During those decades, the then absolute monarch, the late King Birendra — reincarnation of Vishnu, the same God Buddha is also supposed to be the Avatar of — petitioned the United Nations to declare Nepal a “Zone of Peace!” Had he not believed his country and his subjects to be peaceful and against Ahimsa, he probably wouldn’t have petitioned so!

If there were any doubt, patriotic songs of the time told us the country was “Sundar, shanta, bishal” (beautiful, peaceful, [and] grand).

We must have been so then, no? 😀

But…jokes aside, I know what used to happen behind “closed doors,” as it were, when I was growing up. In the absence of data and going with the anecdotal, I would assert that those who attended school with me in Nepal, also know. Furthermore, that those Xaverian friends and I are probably NOT the exception in that knowledge and the underlying experience. In other words, a significant percentage of current adult Nepalis are probably trying to recover from their childhoods as well.

What I am talking about is the tacitly accepted high level of physical and psychological violence that existed in the country then, both in homes (against children and women) and at educational institutions (against children).

Apparently, we in the Indian Subcontinent have, in our Hindu texts, what could be taken as equivalent to the English proverb “Spare the rod, spoil the child.” Found in the version of the Hindu epic Ramayana written by Tulsidas, according to the blog post We can … without corporal punishment, it goes like this: “भय बिनु प्रिति नहोई” (Bhaya binu priti nahoi). Literally, it translates into something along the lines of “Without fear, there is no love/affection.”

In other words, love and affection should be accompanied with fear of punishment (when raising a child).

In Nepali language itself, adults use the following two sentences regularly: “Pitai khanu paryo?” (Do you want to get hit/beaten?) and “Taha lagaunu parchha” (They need to be put in their place/set straight/taught a lesson). (Taha means place or position.)

The former is a standard threat issued by adults to children perceived of as “misbehaving,” which, even in the case of a toddler, could be something as innocuous as being active and running around or asking a lot of questions etc. The latter phrase finds expression in a variety of contexts.

In the highly stratified Nepalese society, everyone has their designated rung (taha) in the social ladder.

The taha where low castes are, for instance, is below the high castes. The taha where the employees are is below the employer. The taha where the low ranking officials are is below the high ranking officials. The taha where the poor are is below the rich. Girls and women’s tahas are below those of boys and men. Similarly, the taha where the children are is below the adults, etc.

These tahas, these rungs where people belong in the social ladder for example, are all reinforced again and again by the social protocols people follow, by the honorific titles people use when addressing one another, by the language we use (e.g. the pronouns we use, the level of formality in our speech other than that which is denoted by the choice of pronouns), by the manner in which those who think of themselves as superior talk about, treat and engage with those they view as inferior etc.

One’s position in the social ladder is also reinforced by those agents in our society who know it all: us, adult men, the all knowing “defender” of culture, keeper of our family “honors,” and “preserver” of our God-given social order!

After all, Nepali society is by men for men, mostly. Thus, boys and men are the more frequent users of the expression “Taha lagaunu parchha” in exchanges between themselves in a variety of different contexts, including when talking about girls (girlfriends), women (wives) and children — especially when perceived of as “displaying behavior unbecoming of their taha.“

Nepali society is also mostly by adults and for adults, mostly old adults.

The young therefore are expected to respect and cede to their “authority” as a matter of course, also mostly. Children (as well as women) “displaying behavior unbecoming of their taha” translates really into “not behaving in a way our male- and adult-dominated society commands and demands.”

When children don’t, adults — parents and other care-givers (such as older siblings, cousins and relatives), and educators etc. — use the threat of, and also mete out, physical and psychological punishments “to put them in their place/to set them straight,” and to let them know who the boss is!

I myself didn’t escape that as a child.

While I can’t recall the number of times I received physical punishments from my mother — because they were regular and, looking back, pretty inconsequential — what I received from my father and my teachers weren’t, though both of them number just one each!

The one I received from my dad was before I started at St. Xavier’s Godavari School while the one at the school happened barely into my first grade. Both the instances of corporal punishments led me, among other things, to resolve to never do anything to bring the wrath of adults (such as my father and teachers) on me, and I never did.

Many of my school mates and others however were nowhere near as lucky.

I grew up watching young children, like myself, being punished in public by adults quite regularly, at times really severely. In addition to beating them, adults would regularly humiliate them by singling them out or by verbally mocking them (calling them by nicknames) or by making them undergo punishment routines (like taking the “chicken stance”) in a part of the classroom everyone could see etc. etc.

The culturally-inculcated belief was, and still is, that punishing and humiliating children will instill, among other things, discipline, the constantly and fervently sought-after end-goal of most caregivers and educators in the country. One of the things they are actually doing, of course, is to (seek to) exert control over them.

One side effect of normalization of violence by adults is the fostering of bullying between children (e.g. siblings), between students, some suffering from consistent and sustained bullying from other children.

I myself was spared the kind and level of bullying that some of my classmates suffered from. The reason, I think, was mostly because of my standing as one of “a good student” — good in academics as well as in behavior.

But, an incident that I feel influenced my relationship with — as well as shaped my attitude towards and views of — my classmates and others in the country to this day took place in fourth grade: I was ostracized by my classmates. That year, some hatched plans to beat me up and run me over with their big cars once we graduated to secondary school.

What primary school children cooks up such violent plans unless they have learned that that is the normal course of action in cases of disagreements, or whatever, with fellow primary school children?!

I also hold the school and domestic-culture of using and accepting physical and psychological violence responsible for some of my classmates conspiring to “teach me a lesson” over something they did not like about my running the show at our one-year reunion. Just a couple of years or so ago, a classmate, even as a middle-aged man, tried to convince me how it was “right” to “settle” disputes involving violence with violence at a later time!

(One of the consequences of the ten-year civil war appears to have been a more pervasive belief in the efficacy of violence as a tool.)

At our all-boys school, many others however suffered considerably more in the hands of fellow classmates and schoolmates for a number of different reasons.

Not surprisingly, many were bullied regularly for “looking like a girl” or for “behaving/walking/talking/gesturing like a girl,” for instance. Classmates gave others nicknames such as “Maiya” (little girl), “Pothi” (hen) etc. Late Alok Nembang was one of the classmates bullied for his effeminate characteristics. (The acclaimed movie director killed himself a few years ago after struggling for a long time to reconcile his lifestyle in the very conservative Nepali society.) Prabal Gurung, the world-renown fashion designer, a junior at St. Xavier’s, I know was also bullied in school for the same reason.

Students bullied and humiliated one another for other reasons too, some much more than others.

Many were humiliated by teachers for not completing a task or for not being able to sing or play a sport well or for performing poorly in a test or for talking back etc.

Based on my conversations with my classmates over the years, based on my observations of how they interact with one another on social media and how they believe others perceive/see/view them even now etc., I have concluded that a significant number of them are still struggling to recover from the long-term impact of both violence from teachers and administrators and bullying and violence from fellow students they experienced at St. Xavier’s School in the seventies and eighties.

Most of my classmates, however, will probably never candidly discuss how those experiences affected them then and continue to affect them now because, as twisted as it sounds, shame is associated with having been such a victim! That stigma ensures conversations in the open remain taboo. Forget about sharing the details of the violence experienced in the hands of our family members.

A few times, at gatherings way back in the nineties, one classmate, in his drunkenness, did share stories of violence he experienced in the hands of teachers as a primary school student. At the time, to me he appeared to recount those memories to not really initiate a conversation and/or to not seek help and initiate the process of healing, but rather as comical anecdotes. We all had a laugh whenever he shared his stories. That classmate, unfortunately, has since passed away. We will never know if, and how, he suffered mentally and emotionally.

Since returning to Nepal in May 2013, I have tried to have serious conversations around this topic, albeit in private, with some classmates but I have not had any success.

Even if shame were not a strong enough a deterrent to sharing their experiences openly, many will probably consider doing so as tantamount to surrendering their culturally-inculcated sense of manhood, no different from most men around the world.

None of this is meant to insinuate that bullying, violence and abuse happened most of the time to most of us in our homes and at our school then. I have no basis for saying that. But based on what I remember and what I have heard since graduating, in 1987, I am pretty confident in stating that we did have enough of them to have been a real issue then.

More than twenty-five years on, after a whole generation have come through, children in Nepal STILL appear to suffer from an inordinate amount of violence.

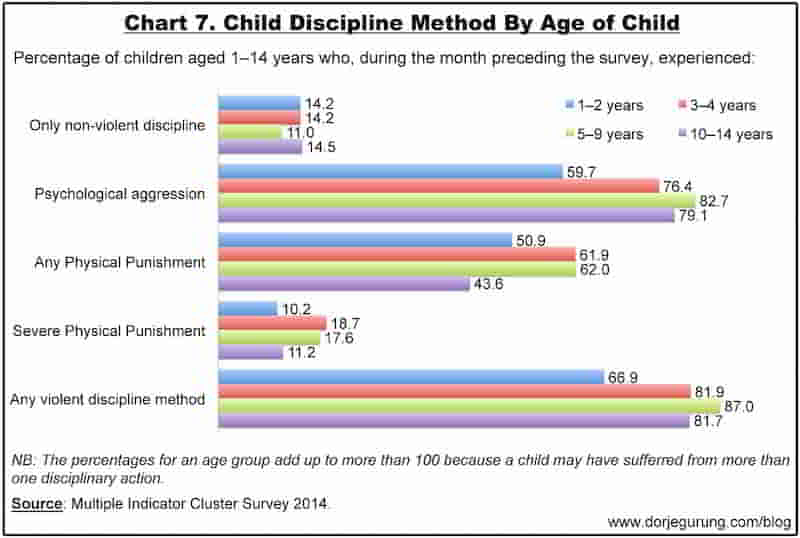

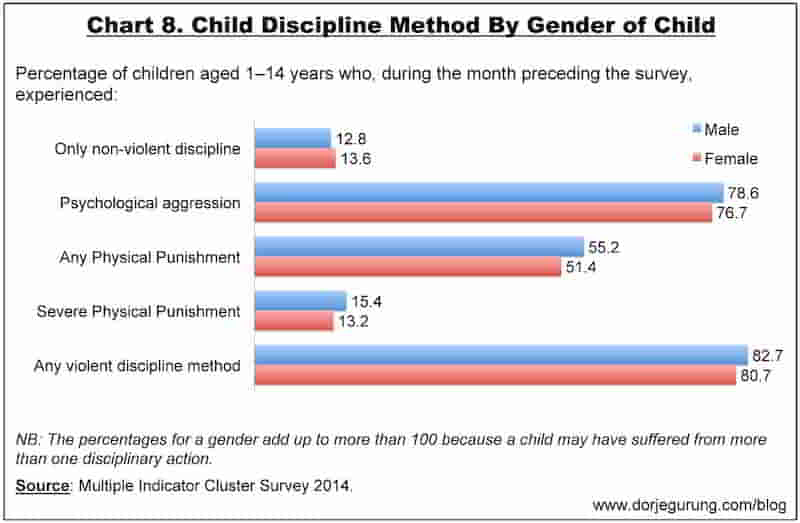

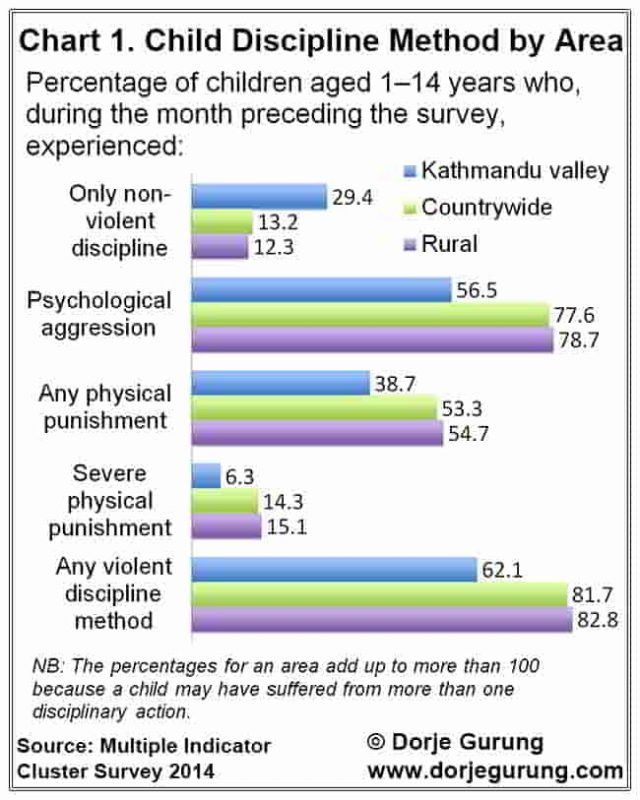

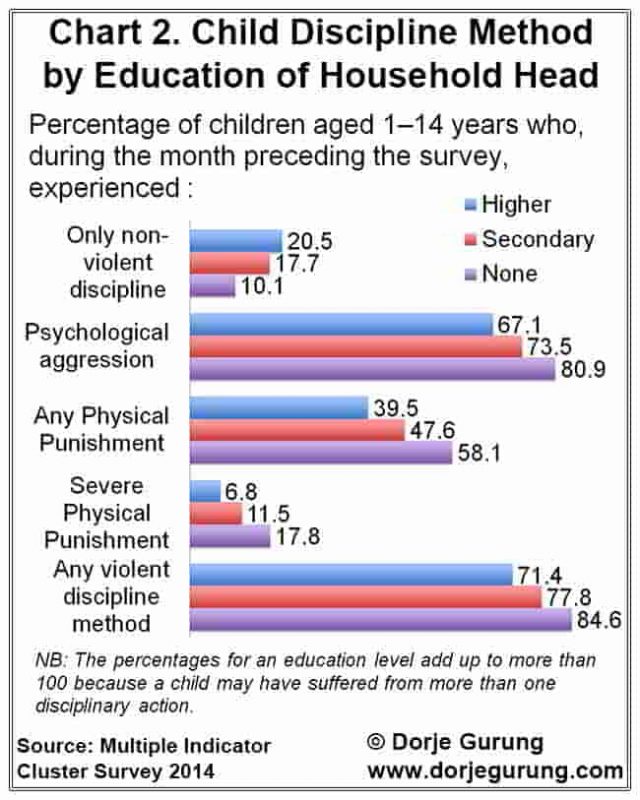

The following are results of “Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2014” (MICS5) on child discipline methods employed by care-givers at home. The charts speak for themselves.

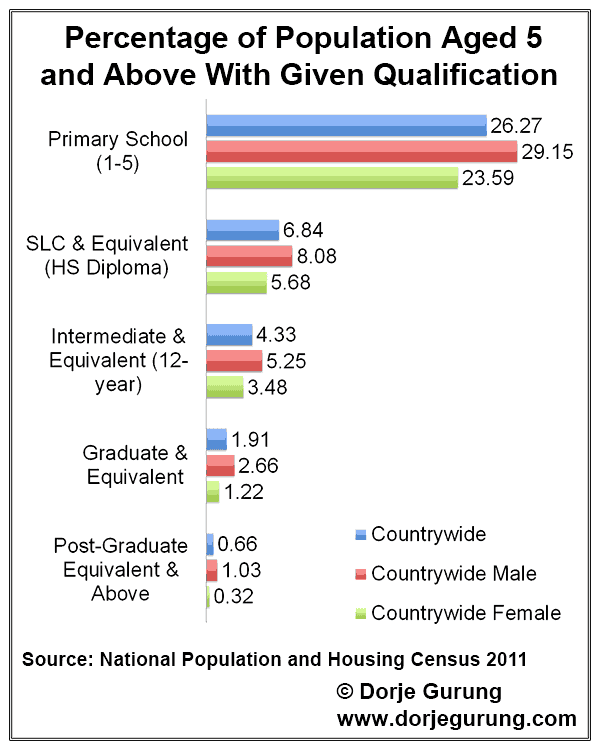

As expected, level of education does appear to influence, a little bit, the discipline method used. However, the percentage of population with education level higher than secondary is pretty low as you will see farther down below.

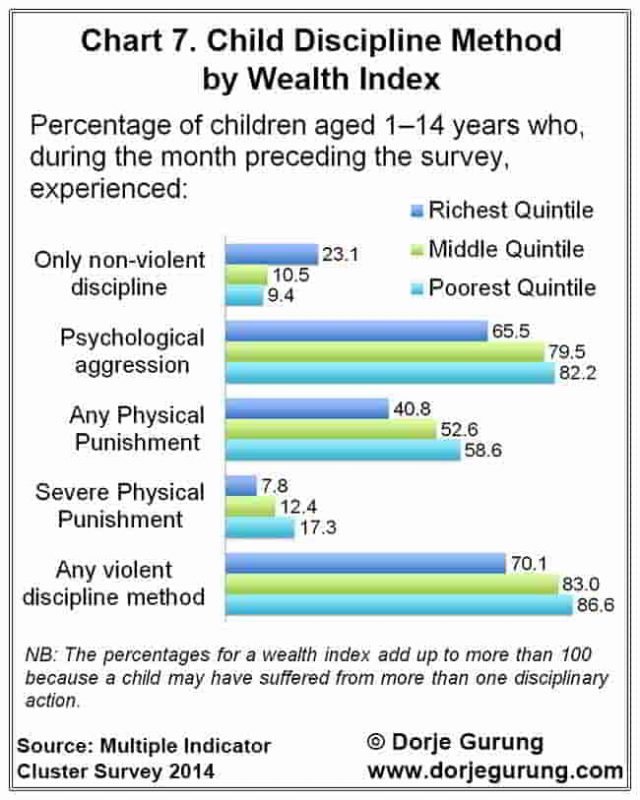

Wealth (as you can see above) also appear to influence, a little bit, the discipline method employed by care-givers.

As you can see, even babies don’t escape violence in the hands of their care-givers. 🙁

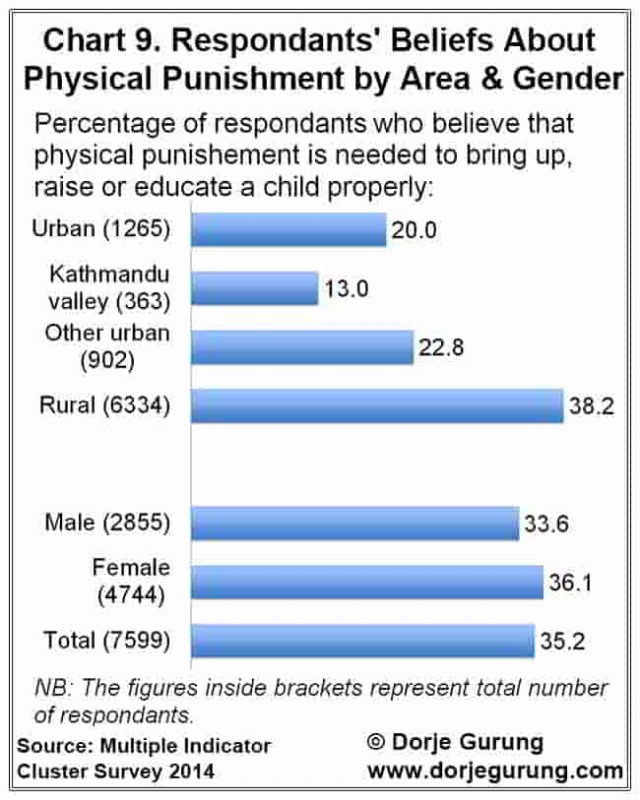

The extent of belief on the efficacy of physical punishment is not surprising given, firstly, the level of education of the population (see image below) and, secondly, the poor quality of education.

As a matter of fact, a recent study of 1500 mothers’ knowledge of mental development of their children conducted by Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital Children’s Health Department discovered that both educated and uneducated mothers had limited knowledge and understanding about the topic, for instance. The author goes on to state how, in her twelve years of experience as a pediatrician, rarely has she had parents inquiring after their child’s mental and intellectual development.

As for violence in schools, a survey conducted by CVICT in collaboration with UNICEF “Violence against children in Nepal: A Study of the System of School Discipline in Nepal” (published in 2004), found it to be widespread.

The 2013 article “Despite Training, Physical and Psychological Abuse Continues in Nepal’s Schools” citing a 2006 study says, “more than 80 percent of students said that their teachers had beaten them.” What’s more, as the headline says, physical and psychological abuse continues.

What must it be like in schools now?

Given that the way most of the children interviewed for MICS5 were disciplined by adults, given that some of the same adults who in MICS5 believe in physical punishment must also be teachers and administrators, I am going to assume that the extent and the kind of discipline methods used at schools in the country must also be similar. Granted, on average, a school teacher or administrator most likely will have a higher level of education than an average parent.

A significant proportion of teachers, however, don’t have the necessary qualifications apparently. Even teachers who do hold teaching qualifications, I have been told, don’t know much about child psychology — about their physical, mental and intellectual growth etc. — because none or little of that is part of the curriculum. So, they might not necessarily view and treat students any differently from the way their own teachers did them and the way most of the rest of the adult population do.

Is it any wonder then that, on the Societal Violence Scale (SVC), when it comes to violence against children, Nepal, in 2014, scored a 4 out of 5. (The higher the score, the more violent a society.)

Here’s the descriptor for level 4:

Reports of violence against the group are pervasive in scope as well as severe in nature and may assume a variety of forms. It affects a significant proportion of the group. [Emphases mine.]

What raising children with violence does, as summarized in Multiple Indicator Cluster Studies 2014, borne out by results of extensive research, is the following:

“[E]xposing children to violent discipline has harmful consequences, which range from immediate impacts to long-term harm that children carry forward into adult life. Violence hampers children’s development, learning abilities and school performance; it inhibits positive relationships, provokes low self-esteem, emotional distress and depression; and, at times, it leads to risk-taking and self-harm.” (p. 186)

Violence at home and in school is not limited to only the physical and psychological (emotional and mental), of course.

I am pretty certain that children in Nepal also suffer from sexual violence/abuse. As has already been hinted at earlier, stigma and taboo surrounding violence in homes and schools is still strong. That must partly explain their prevalence.

To date, I have read just three personal accounts by Nepali writers about child sexual abuse they experienced growing up in Nepal. The first, Kathmandu Girls, is a blog post by Jemima Diki Sherpa about her experiences of sexual abuse and harrassment.

Jemima @whathasgood recounts powerful, vivid stories of sexual harassment in #Nepal…”shameful” stories. https://t.co/VaNGTYaTgZ

— Dorje Gurung (@Dorje_sDooing) February 10, 2016

The second one, Silence and Shame, is by Niranjan Kunwar. In the article, he recounts the “shameful” story of his sexual abuse in the hands of older students in 1993. He goes into the details of why cultural stigma is still associated with being a victim and how he was treated to very very uncomfortable and obvious silence by others.

Maybe the first personal account of #sexualabuse experienced as a student in #Nepal that I have read. https://t.co/ivfQPmUZUq

— Dorje Gurung (@Dorje_sDooing) February 10, 2016

The third one, by Aastha Kumari Karki, is about her harrowing experience of being raped by an older cousin from six to twelve. I have reproduced her story here.

Violence — ALL forms of violence, and especially sexual violence — CAN also leave children with trauma which have both short-term and long-term impact on their lives.

I can tell you from experience that recovering from trauma — any trauma — is a challenge, is a real struggle. There are probably many in Nepal who haven’t even realized how the violence they experienced as a child has affected and shaped them. Because of the strong stigma associated with the experience and the taboo surrounding conversations about social ills such as this, they would have had very little or no opportunity to talk about and explore that aspect of their experience.

If we as a country continue to use, condone, and abet — by our reluctance to firstly acknowledge the existence of and secondly to talk openly about — such “pervasive” and “severe” violence on children, we’ll continue to raise children who will have to “recover from their childhoods.”

The first path to addressing this issue, obviously, is to lift the veil of stigma surrounding it by acknowledging the problem and to eliminate the taboo surrounding it by creating a safe environment for people to come forward and talk about it.

Writing this blog post is my small contribution towards that.

The other reason for blogging about this is to point out that firstly, we have laws against it.

And secondly, that we need to start raising awareness in schools and homes about its existence and to push for its enforcement.

The final reason for this blog post is to say that it is indeed possible to both raise and educate children without threatening them with — or using — violence.

Just because violence is part of our culture, as I keep being told again and again, including by a friend who owns and runs a school, doesn’t mean that we as Nepali people won’t be able to do without it.

I, a Nepali, have raised a little nephew at home without ever meting out any physical punishment during the little boy’s entire six years of life on this planet. I have also instructed his school that no one is to mete out corporal punishments to him. I am pretty certain that they haven’t.

As an educator in my previous career of 15-plus years as a science teacher too, I NEVER once meted out any violent punishment to students whether in Nepal or outside.

I am NOT some incredibly gifted care-taker to my nephew nor am I some outstanding teacher with incredible classroom management skills etc. I really am not; I wish I were.

Yes, I am fully aware of the fact that I have been educated in five countries, have taught in ten and have traveled in another thirty or so countries, and in that way I am very very different — in education, experience, awareness, outlook etc. — from a vast majority of Nepalis.

BUT, I still remember how I felt as a child being on the receiving end of, as well as a witness to, violence from adults, and, even then, I didn’t want that treatment.

I didn’t want my teachers (and fellow students) to treat my classmates and schoolmates the way they were. I am pretty certain that speaks for pretty much every Nepali adult who experienced physical and psychological violence as a child. Furthermore, as an adult, I assume that children now don’t want to be treated that way either!

I am also aware of how those experiences of violence negatively affected and shaped me. I certainly, therefore, don’t want that to be the case with children under my care if for no other reason than just that!

In other words, I am sure most of the rest of adult Nepalis, who were also victims of such violence as children, know and are aware of that which happened to them, why they didn’t like it, and many are probably aware at least a little bit of how that has now affected them as adults and, I assume, wouldn’t want that for children under their care.

Anyway… while we create an environment where those who are recovering from their childhoods have a voice, “let’s raise children who won’t have to recover from their childhoods.” Let’s raise children to be kind and compassionate human beings instead!

More than any kind of person, I truly believe that our country and the world needs more kind and compassionate human beings and the goal of every care-giver and educator should be to raise children to be just that.

In an effort to ensure that my little nephew does NOT have to recover from his childhood the way I am having to, I am, deliberately and consciously, raising him to grow up to be a kind and compassionate human being. And violence has no place there.

What do you think? Were you a victim of childhood violence? If you are comfortable, feel free to share your experience in the comment section or by email.

* * * * * * * *

References

- Nelta Choutari (July 2012). We can … without corporal punishment. “According to Tulsikrit Ramayan, Ayodhyakand, one of Hindu religious books “भय बिनु प्रिति नहोई” (which means that there can be no love or motivation that leads to success without punishment/fear).”

- The Himalayan Times (June, 2017). Behind plane crashes: Cultural aspect. “It’s not our culture to question a superior authority. This particular tradition is seen in offices, families, schools, and security agencies and in every layer of our society.”

- Nepali Times (November, 2014). Lights Off.

- UNICEF (2014). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2014: Monitoring the situation of children and women.

- The Kathmandu Post (March, 2017). Quality continues to remain major challenge.

- Kantipur (June, 2017). आफ्नो बच्चाबारे हामीलाई कति ज्ञान छ ? (How much do we know about our children?). “अहिलेसम्मको अनुभवमा बिरलै कुनै पनि आमा वा बुबाले मेरो बच्चाको मानसिक विकास कस्तो छ वा कसरी बच्चालाई तेजिलो बनाउन सकिन्छ भन्ने प्रश्न सोध्ने गर्छन् ।” (“In my [twelve years of] experience as a pediatrician, rarely have I had a parent inquiring how their child’s mental and intellectual development is progressing and how they might be able to help in the process.”)

- UNICEF (2004). Violence against children in Nepal: A Study of the System of School Discipline in Nepal

- Global Press Journal (June, 2013). Despite Training, Physical and Psychological Abuse Continues in Nepal’s Schools.

- Political Terror Scale. The Social Violence Scale (SVC): Explained.

- Political Terror Scale. Societal Violence Scale (SVS) dataset.

- Psychology Today (April 29, 2016): Update On What Really Happens When You Hit Your Kids. 50 years of research on 160,000 children shows spanking is harmful. Period.

- What Has Good (February 2013). Kathmandu Girls.

- Himal Southasian. Silence and shame. “A Nepali man’s struggle to get the incidence of sexual abuse as a child acknowledged in a society that does not want to talk.”

- Psychology Today. What Really Happens When Parents Hits Their Kids. Summarizes the important findings of a meta-analysis of “50 years of research on 160,000 children shows spanking is harmful. Period.”

- Psychology Today. This is What Happens When You Hit Your Kids.

- WHO. Violence Prevention The Evidence. A brief on how cultural and social norms promote violence and how they can be tackled.

- Journal of Nepal Paediatric Society (May-August, 2010). Corporal Punishment in Nepalese School Children: Facts, Legalities and Implications.

Additional References

These don’t appear in the blog but are relevant to the topic.

- ASCD (2006). Research Matters / Promoting Adolescents’ Prosocial Behavior. “All infants are born with some empathetic ability that enables them to connect emotionally with other human beings (Sagi & Hoffman, 1994). As children grow up, however, the development of this innate empathy depends on their relationships with others. For example, children whose parents express warmth and responsiveness to their needs are more likely to develop prosocial behaviors (Zhou et al., 2002).” Emphasis mine.

- Scary Mommy. It’s Time To Quit The Abusive Practice Of Mocking Children’s Emotions. In Nepal, it’s quite common for adults — whether parents, older relatives, older siblings, cousins, or any care-giver and even educators — to use shame to control a child’s behavior. This article describes very well why we shouldn’t.

- UNICEF (2009). Learning the child-friendly way at UNICEF-supported schools in Nepal. This is just one article I have come across which says that changes in the way teachers treat students have been observed (in the 1000 schools in 15 districts their trainers have reached since 2002). “As there is no more physical punishment in the school, children are more vocal about their needs and demands. This has helped to boost their morale and confidence.”

- This video on Facebook shows three little girls at a school in Kathmandu being humiliated for some transgression. The cultural belief is that humiliating children (and using corporal punishment) will teach them about “discipline,” which in Nepal actually means pliant, subservient, and obedient to adults and authorities. In other words, to Nepalis, the word does not denote what it does in English. Incidentally, what they are doing is the “chicken stance.” It involves squatting, inserting ones hands between the thighs and the calves and grabbing the ears! Some teachers might even require that they pull on them hard! [Added on Sept. 11, 2018.]

- NPR (Oct. 25, 2018). What Happens When A Country Bans Spanking? “Now a new study looking at 400,000 youths from 88 countries around the world suggests such bans are making a difference in reducing youth violence.” [Added on Oct. 26, 2018.]

- NCBI (July 10, 2013). Spanking and Child Development: We Know Enough Now To Stop Hitting Our Children. [Added on Oct. 26, 2018.]

- My Republica (Oct. 29, 2018). How GEMS created “villains” & “bad students.” Ten years later, a former student recounts his experience at GEMS school, a private school in Kathmandu, where the school culture included corporal punishments. [Added on Oct. 30, 2018.]

- The Record (Dec. 4, 2018). Youngsters battle severe emotional and psychological stressors. “Changing the culture of silence surrounding mental illness could save lives.” [Added on Dec. 6, 2018.]

- The Kathmandu Post reporting on a history of sexual abuse of girls by a teacher at a school in the valley. The first article (published on Jan. 26, 2019): Maths teacher at Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidyalaya sexually abused young girls for decades. “Some of the parents asked the Post not to report the story and that they would find a way to resolve the issue internally.” …”She [the Vice Principal] then asked the Post to rethink running the story and that they would resolve the issue internally by taking action against Tripathee.” Saving face for some adults in Nepal is still so much more important than the bigger issues, unfortunately! Follow up to it (published on Jan. 27, 2019): Lalitpur school says it has suspended—not removed—the teacher who sexually abused girls for decades. The third one (Jan. 27, 2019): Tears and anger at a Lalitpur school after revelations about a teacher’s history of sexual abuse.

- The Himalayan Times (Feb. 17, 2020). Teacher accused of molestation, primary schoolgirls request school authorities for investigation. “Teachers were divided on whether to take legal action against Niraula or not. Some argued that ‘it would give a bad name to the school’.” [Added Feb. 17, 2020.]