Growing up in Nepal, I endured verbal, emotional, and physical violence, along with deep humiliation. I wasn’t a mischievous child; on the contrary. This abuse stemmed from the traditional, harsh belief among Nepal’s population that children should be spoken to, not listened to. Psychology proves that such violence inflicts long-lasting damage on a child’s emotional development, severely influencing their lives as adults.

Leaving Nepal as a teenager for Italy to study at the United World College of the Adriatic offered me a completely different social and cultural context. It was there I began discovering a great deal about myself, among a host of other things.

One of the many discoveries I made was regarding feelings: I had hardly ever been asked about them by my care takers or teachers or friends. I remember not understanding my girlfriend’s question when she had asked how the painting we were viewing made me feel. The other thing I discovered was that I didn’t really know how to regulate and/or manage my emotions. In relationships, I gave into them. More often than not, I reacted emotionally to even things that I shouldn’t.

Crucially, as I continued my education abroad and had more relationships, I realized that not only did I not pay sufficient attention to my feelings and emotions, I could hardly articulate or express them. It was as if I literally had no words for them, because neither my formal nor informal education systems had ever taught them to me.

I discovered just how much Nepal’s culture—at home, school, and in society—had failed to cater to my emotional needs, and those of children in general. A clear consequence of this neglect is that such children grow up to be emotionally stunted and immature adults just as I had. This immaturity is the source of many issues Nepalis—especially males—face when trying to express themselves in general and when trying to manage, or regulate their feelings and emotions.

The National Impact: A Broader Problem

A Nepali man, whom I don’t know personally, recently discovered just that and made a Facebook post about it. I learned about it after a mutual friend commented on it, tagging me and saying I “often write about Nepali culture.” So I took the opportunity to respond. But before my own comment, here to begin with, is a verbatim reproduction of the post. Please note: To protect privacy, I have used only first names.

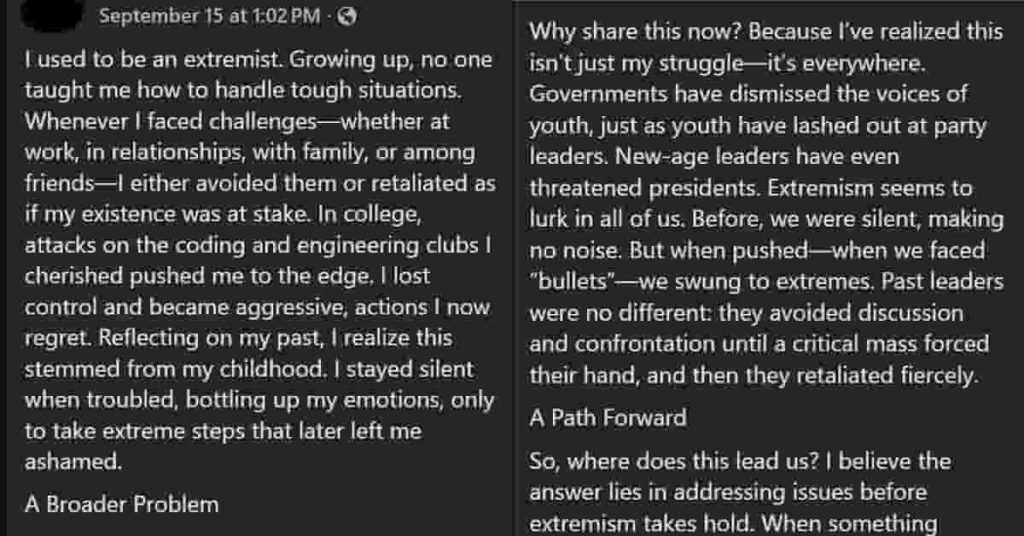

I used to be an extremist. Growing up, no one taught me how to handle tough situations. Whenever I faced challenges—whether at work, in relationships, with family, or among friends—I either avoided them or retaliated as if my existence was at stake. In college, attacks on the coding and engineering clubs I cherished pushed me to the edge. I lost control and became aggressive, actions I now regret. Reflecting on my past, I realize this stemmed from my childhood. I stayed silent when troubled, bottling up my emotions, only to take extreme steps that later left me ashamed.

A Broader Problem

Why share this now? Because I’ve realized this isn’t just my struggle—it’s everywhere. Governments have dismissed the voices of youth, just as youth have lashed out at party leaders. New-age leaders have even threatened presidents. Extremism seems to lurk in all of us. Before, we were silent, making no noise. But when pushed—when we faced “bullets”—we swung to extremes. Past leaders were no different: they avoided discussion and confrontation until a critical mass forced their hand, and then they retaliated fiercely.

A Path Forward

So, where does this lead us? I believe the answer lies in addressing issues before extremism takes hold. When something troubles us, we must engage in discussion, discourse, and reasoning. We should reflect on what’s being said and clarify misunderstandings. To those who feel heroic in their extreme actions: it’s time to reflect on your trauma. Dialogue and self-awareness can break this cycle of avoidance and overreaction. Let’s choose understanding over escalation.

Here’s my response with minor changes.

[Niranjan], any Nepali who has truly introspected and reflected on who they are, how they are, and earnestly wondered why they are the way they are will have discovered what Bibek did.

Of course, there are MANY reasons behind that and what Bibek says about what we should do is a step forward. BUT Nepalis need to REALLY deeply reflect on our education system–both formal & informal education system–shaped as it is by the caste-based, age-based, and gender-based stratified and hierarchical [Nepali] society and punitive culture.

As children, as females, as lower castes, as juniors in the office, etc., Nepalis are taught—at school, at home, in offices, in public places, etc.—to obey, to follow rules, to be “disciplined,” suppressing our feelings and emotions. We are NOT taught to question and to seek knowledge and understanding. We are NOT really taught to seek connections. We are NOT taught about our emotions, about how to feel, and how to express them, let alone determine and chart a path for our own personal inner journeys.

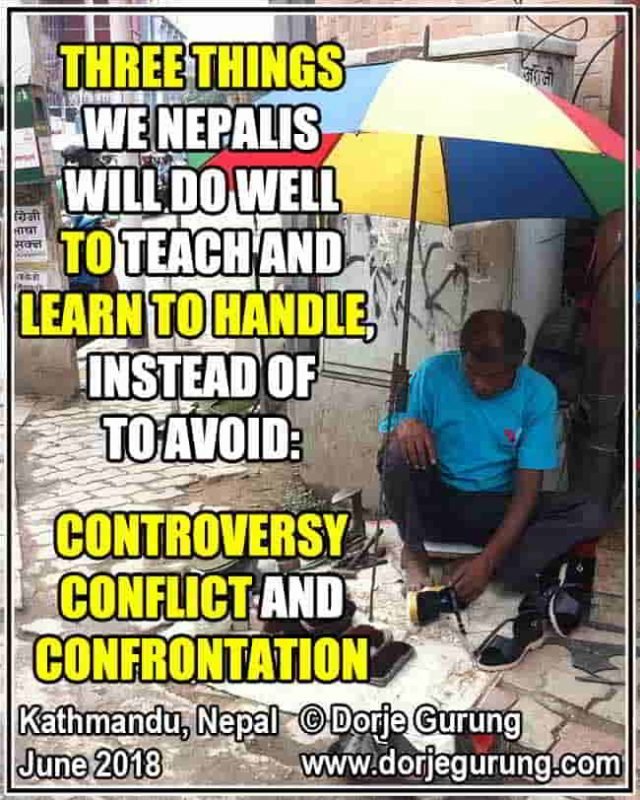

One of the many consequences of that is that we don’t learn to deal with or handle controversy, conflict, and confrontation. By default, we end up AVOIDING them. But of course, as you figured out Bibek, you cannot do that all the time. And so, periodically, you have to release some of that pent-up frustration and anger. [The image that appears below as part of my response.]

Unfortunately, not having been taught how to release them in non-destructive ways, Nepalis, especially men, more often than not end up venting them in destructive ways and/or at people who are not necessarily responsible for the frustrations and/or anger within.

I know all that from having been an educator all my life, having taught in 10 countries around the world including in Nepal. Good luck with your movement forward from here onwards having discovered what you have about yourself. Your inner life will improve.🙏

What my response does not delve into is the root cause: children are forced into being “obedient,” “good,” and “disciplined” through the persistent threat of violence. Verbal, emotional, and physical violence are routine against children in schools and homes, and against females, and Dalits. Those in lower professional positions also suffer from verbal and emotional violence in work places in Nepal.

This environment can mean suppressed and unaddressed frustrations manifesting even as random public violence, particularly among males. Males talking about settling issues and scores violently and carrying it through is not uncommon. Recent protests, for instance, have shown highly frustrated men venting their bottled-up anger—the only release they’ve been taught.

I am not justifying the violence perpetrated by the police or the public, nor claiming that every participant acts from personal trauma. However, this deep-seated, traumatic cycle of violence is an undeniable factor, which, as Bibek discovered, profoundly shapes adult emotional life.

The Path Forward

While Bibek’s suggestions for ‘A Path Forward’ are greatly helpful for adults, a general cultural shift is necessary for society as a whole. When it comes to raising and educating children, we must cater to their emotional needs.

Respecting Developmental Needs

Nepali tradition wrongly views and treats children as if they were miniature adults in many contexts, while, simultaneously, denying them the respect they accord adults. Science clearly shows children aren’t physically, emotionally, or intellectually mature; they have needs very different from those over the age of twenty-five.

For example, young children simply lack the developed brain capacity to regulate their emotions—expecting them to control their feelings is unrealistic and harmful. While teenagers’ brains can regulate emotions better, the sheer volume of hormones flowing through their veins, for example, makes them impulsive, taking uncalculated risks with very little to no regard for long-term consequences. A human brain isn’t fully developed until around age twenty-five. Therefore, children benefit greatly when adults engage with them at their appropriate social, emotional, and intellectual level.

Validation Over Punishment

Meeting emotional needs fundamentally amounts to respecting children. The most effective way to demonstrate this is by listening to them—whether they are being emotional by crying, screaming etc., or sharing feelings, or simply speaking about anything.

After listening, meeting their needs means validating their feelings and teaching them about their feelings and emotions: why they feel and react the way they do and what they can do about it, if anything. This includes giving them opportunities to explore their emotional world by, for example, asking for their opinions on decisions that affect their lives.

Children who are emotionally neglected or traumatized will lack major skills as adults, notably managing their emotions. Nepal’s culture is, by contrast, highly punitive.

Far from creating spaces for children to make mistakes and learn from them, this punitive culture instills such a deep fear of failure and a sense of hopelessness that some are too afraid to take risks, while at the other extreme, some are driven to suicide. The toll is devastating: according to child psychologist Dr. Pasupati Mahat, Nepal is ranked third in the world in adolescent suicide rate. Worse still, official data from 2019 to 2024 show that girls kill themselves at almost twice the rate of boys.

Instead of punishing a child for a mistake, we must teach them alternative behavior, explain the reasoning behind it, and give them opportunities to practice it or demonstrate it. This places a higher value on emotional well-being, and the change is likely to be long-lasting. Apparent behavioral change brought about by the threat of violence is never truly internalized.

Core Education Reforms

To create a system that fosters emotional maturity, the following concrete steps are necessary:

- Impart critical thinking skills, which naturally will foster the innate curiosity in children. This makes them question things and to express, and speak up instead of being ‘disciplined’ and ‘good’ and bottling up their feelings and emotions.

- Actively integrate students by gender to promote mutual understanding and reduce gender-based hierarchical divisions in the classroom. Schools must also introduce a comprehensive and thorough human reproduction and sex education program. This subject fosters crucial curiosity, empowering students to learn about themselves—who they are, what’s happening to them, why, and what they can do to facilitate their physical, mental, emotional, and intellectual growth.

- Actively integrate students by caste and introduce formal education on the caste system. This instruction must develop an understanding of how the caste system affect some more than others. By teaching students about the system’s historical and contemporary impacts, schools can foster empathy for those whom Nepali society views and treats as less than, particularly the Dalits.

- Schools need to formally teach conflict resolution, if at all possible. If not, they should do so informally, as opportunities arise constantly within school compounds. Doing so will impart skills to better deal with controversy, conflict, and confrontation.

What do you think?

PS. I got help from AI writing this blog.

Additional Reading

About violence in homes and schools in Nepal.

- Raise the Child, NOT the Rod

- Child Discipline Methods in Nepal By Regions, Zones etc.

- “Let’s Raise Children Who Won’t Have to Recover From Their Childhoods.”

- Physical Abuse and Violence: Harrowing Childhood Story of a Friend

- As Much as We are Products of Our Culture, Education, Society etc. We are Also Their Shapers

Alternatives to violence at homes and schools

- Picking Up the Slack: Preparing Children for The 21st Century

- Educating My Little Nephew

- Child Rearing and Education: “Best Discipline” Through No “Disciplining”

- “Nothing is more despicable than respect based on fear”: Want Respect? Show Respect!

- Raise And Educate a Child By Showing Respect

- Nepal, Cultivate a Child’s Mind Instead of Controlling It

- How to and Why Educate and Raise Children to be Compassionate

- Adults Go from Awareness to Attitude to Behavior, While for Children It’s the Reverse