The upcoming elections in March 2026 are unlikely to signal an end to the systemic malaise that has stultified Nepal throughout its 250-year history. While the faces in the Singha Durbar may change—as we saw so vividly during the toppling of the Oli government last September—the root causes of the country’s extractive and exploitative political and economic institutions remain entrenched. For centuries, Nepal has navigated a form of internal colonization by traditionally dominant groups—specifically Khas-Arya men. The period following the 2022 election, and even the current interim administration, has proven to be no exception, maintaining a pattern of rule that has persisted since the 1990 democratic dawn and, indeed, since the nation’s founding.

The Gen Z Revolution of 2025 was a seismic event; the sight of the Parliament building in flames and the historic appointment of Sushila Karki as the first female Prime Minister felt like a definitive break from the past. Yet, as the smoke clears and we approach the March 2026 polls, a sobering reality emerges: the uprising removed individuals, but it left the architecture of power intact.

While the streets demanded an end to the ‘#NepoBaby’ culture and ‘recycled’ leadership, the major parties have retreated into survival mode, entrenching themselves within to the same Khas-Arya-dominated structures that have always protected their interests. Even a leaderless, digitally-coordinated revolution struggles to dismantle a system that has had two and a half centuries to perfect its own preservation.

The Mechanics of Political Hegemony

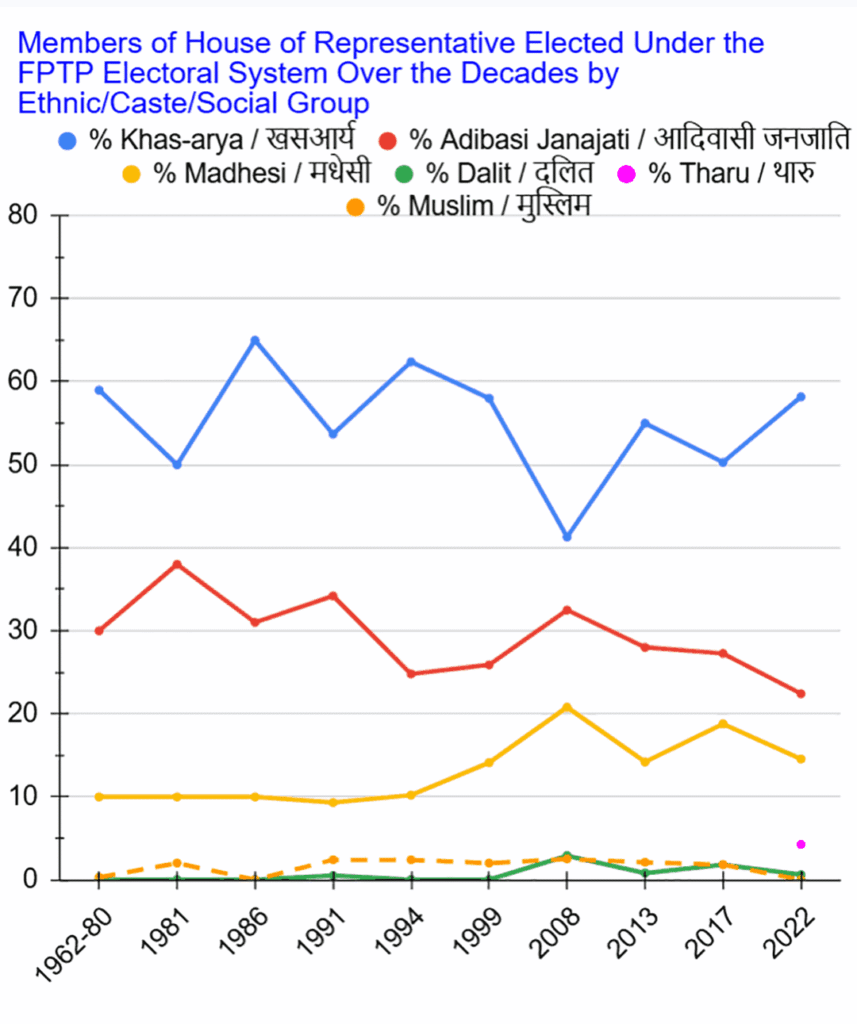

Before 1990, dominance was secured through the crude levers of monarchical and familial connections. In the modern era, the tools are more sophisticated: electoral mechanics.

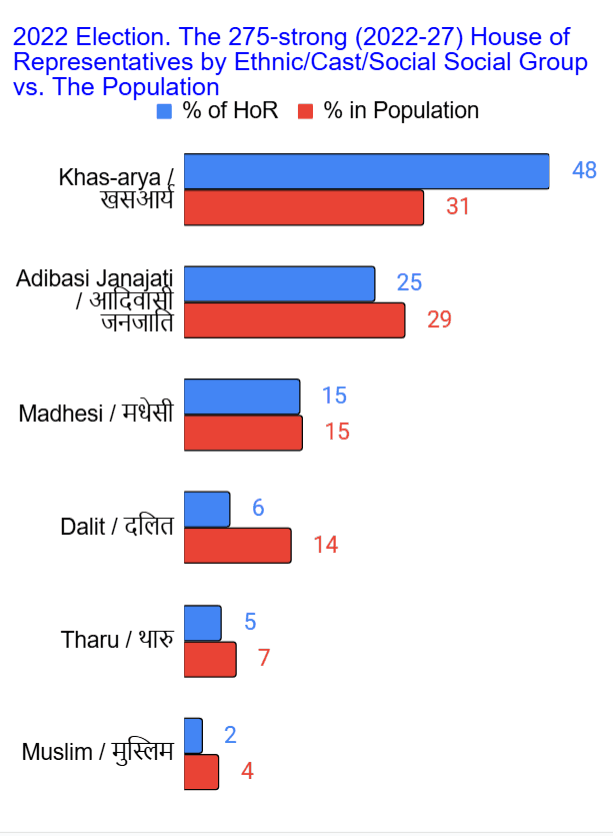

Because Khas-Arya men represent the most over-represented demographic in the House of Representatives (HoR), their parties wield disproportionate power over the Executive Branch. This control cascades into the Judiciary and other vital democratic institutions, creating a self-reinforcing loop of influence.

For tangible political transformation to occur, this hegemony must be dismantled. This requires two primary, yet unlikely, shifts:

- The thorough defeat of the “Big Three”—the Nepali Congress, the CPN (UML), and the CPN (Maoist Centre).

- A recalibration of representation where Khas-Arya presence falls below a plurality in the HoR.

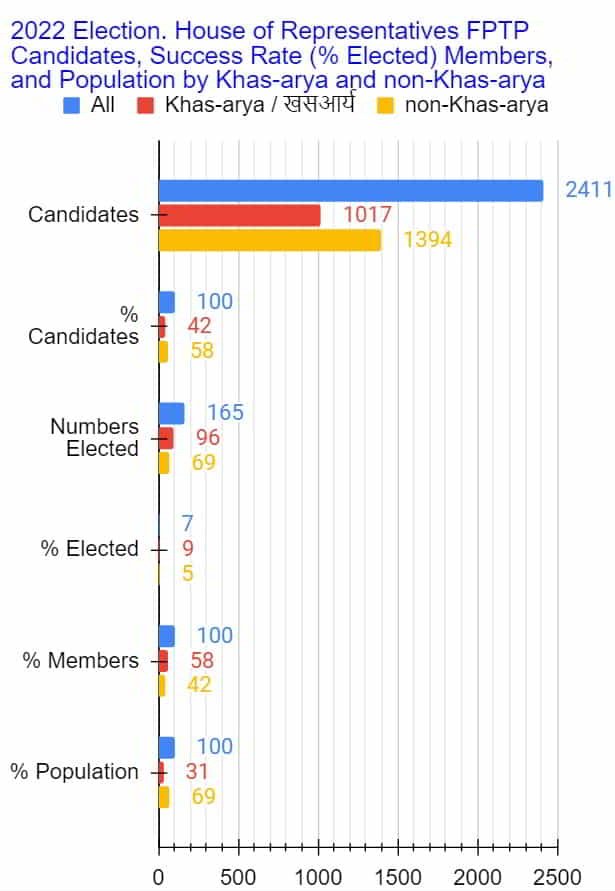

The data, however, paints a grim picture. In the 2022 elections, 58% of the 2,411 First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) candidates were from marginalized groups. Yet, Khas-Arya candidates secured 96 of the 165 seats—roughly 58% of the total—despite constituting only 31% of the national population, not much different from how it has been for decades.

The Proportional Representation Loophole

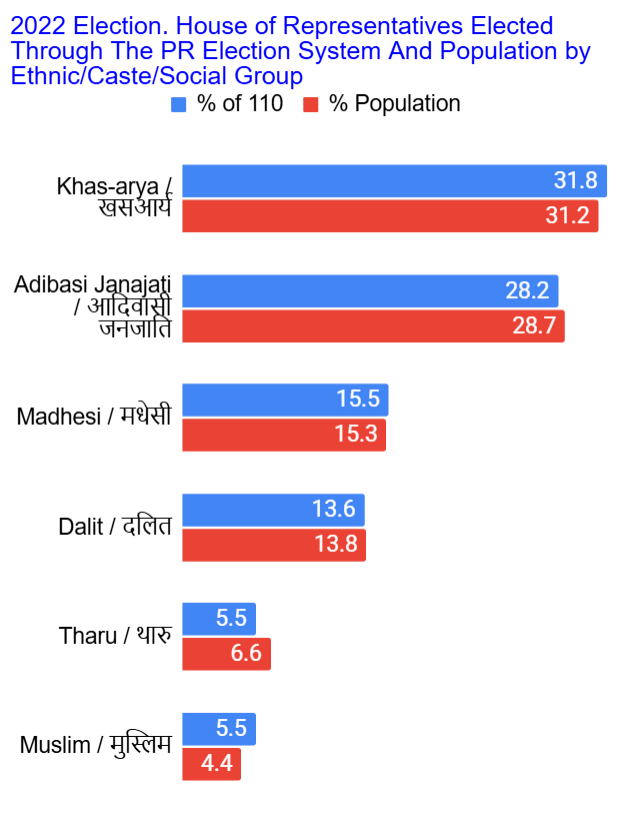

The Proportional Representation (PR) system was designed as a corrective lens for the biases of FPTP. However, the framers of the 2015 Constitution—architects of the established party leadership—cleverly ensured that “poor Khas-Arya” groups remained eligible for PR seats. Consequently, the PR system merely mirrors the census rather than correcting the imbalance of the FPTP results.

The result? A House of Representatives where Khas-Arya members held 48% of the seats. This disproportionate plurality ensured that the largest national parties—and the status quo they represent—remained imperative and unchallenged.

A Culture of Political Self-Interest

Nepal currently hosts over 120 registered political parties, yet few pose a genuine threat to the established trio. To dismantle this hegemony and ensure Khas-Arya men no longer hold a disproportionate plurality, their success in the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) system must be radically curtailed.

Specifically, Khas-Arya representation in the FPTP category must be kept below 50 seats (30%) of the 165 available members. This means the electorate must vote in less than half the number of Khas-Arya candidates compared to the 2022 cycle. Without this specific, statistical reduction, any talk of “new politics” is merely a cosmetic adjustment to a 250-year-old script.

But how many of these new parties are actually forming the alliances necessary to beat the “Big Three”? Historically, the outlook is grim. The 2022 elections revealed a cynical truth: major parties often collaborate to protect senior leaders rather than competing on policy. Even as we approach March 2026, we see the “musical chairs” of leadership continuing, with the same power-brokers negotiating seat-sharing to ensure their own survival.

Furthermore, because party leadership determines “tickets,” candidates remain more accountable to their patrons than to their constituents. Even if a new generation of leaders from outside the trio emerges, they inherit a political culture that prioritizes party survival over national progress. The likelihood of a new class working against its own structural self-interest remains remarkably low.

Education: The Foundation of the Status Quo

The ultimate barrier to progress is a strategically undereducated population. This is not an accidental oversight; it is a calculated omission. We saw this strategy manifest in yet another aggressive form on September 4, 2025, when the state imposed a nationwide social media ban. This was not a mere regulatory hurdle; it was a preemptive strike against a generation that had begun using digital platforms to elucidate and critique the blatant nepotism of the ruling elite.

The ban, intended to stifle dissent, instead precipitated a revolution. Yet, the long-term efficacy of such state control relies on the failure of the Nepali education system, which functions as a permanent gatekeeper. By depriving the masses of the critical tools to navigate state-sponsored censorship and grasp the extractive and exploitative nature of their own economic structures, the elite ensure these systems remain unchallenged.

Until the education system is transformed to produce citizens capable of elucidating, critiquing, and actively challenging these 250-year-old power structures, the cycle of exclusion will persist. The March 2026 elections may offer new ballots, but without a newly educated citizenry, they offer only the same old ghosts in a different booth.

What do you think?

PS. This post is a much longer and comprehensive version of an Instagram post I made on Jan. 14. Additionally, I got help from Google’s AI Gemini drafting this blog post.