When a bunch of us cousins headed to Pokhara late last month, three evenings of celebrations had been in the cards. A funeral? No. But that’s what we got too! 🙁

The celebrations included a wedding the first evening, solid-food feeding ceremony of a cousin’s baby the second, and first birthday celebration of a baby the third. Half past midnight of the final night, just a couple of hours after the last celebration ended, the passing of a maternal uncle followed. 🙁

He had been suffering from terminal cancer, and so his passing was expected. But naturally, as with the passing of any individual at any time, under any circumstance, it came as a shock to everyone.

For the first time in my life, I attended a funeral. Some of the rites and rituals were also new to me. While I have vague memories of attending a ritual here and a ritual there, I don’t really remember clearly why they were held and when etc.

Attending the funeral rites, I was, again, reminded of some of the things I had lost living abroad for as long as I did!

One of the many reasons for wanting to “escape” from Nepal had been to learn about the world and people. But the combinations of Nepali society forcing me to deny my heritage while growing up (click here and here for more on that), growing up in Kathmandu when most members of my community of ethnic-Tibetans lived in Pokhara, leaving the country at an early age, spending pretty much all of my adult life abroad AND in a number of countries meant missing out on participating in, and learning about, many aspects of my own culture and tradition.

One such was funeral rites and rituals and their meaning and significance.

I have always known about, and have seen in movies and documentaries, some of Tibetan death rituals but I really didn’t know the specifics of what, how and why we, Tibeto-Nepalese from Mustang, did them.

Something I have always known is that in Mustang District — and probably in other Mountain region of the country as well as in Tibet — dead bodies are given sky buriels. The body is chopped up and fed to the birds. The video below of a sky buriel in Dolpo is done pretty tastefully if you are interested. However, it takes some liberties with the narration (even if by the inimitable David Attenborough).

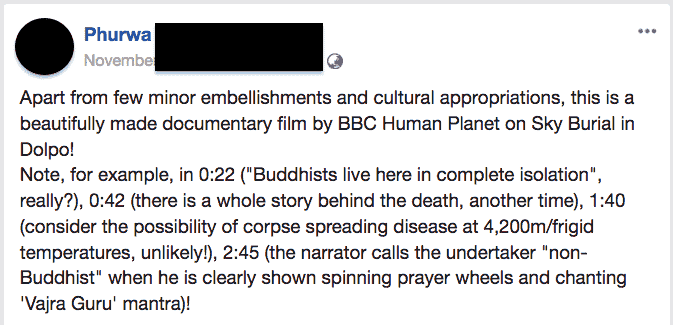

As for the liberties, a Facebook friend Phurwa neatly summarizes them.

While such a practice might be appropriate in the dry, highland deserts of the Mountain Ecological Zone, it’s highly inappropriate in the hills and lowlands of the country.

I knew my community had adapted to the Hindu practice of cremation instead. Responding to the need and demand of such Tibetan-Buddhists in Pokhara, a monastery had set up a cremation site where my uncle was cremated (see below). And that’s where my knowledge of funeral rites pretty much ended! Everything else that followed (and will follow) was mostly new to me.

During cremation, a small bone was collected from the funeral pyre.

The bone symbolizes the person’s atman (soul), which is supposed to be just wandering around lost, unaware that the body has died. Four rites and rituals performed on four different days following cremation, all performed at home, are meant to help the atman find its way to the next world in the Samsaric life cycle.

The first of the four rites and rituals is performed on the third day (called shyak soomba) when the bone is incorporated into a figure symbolizing the deceased person. This ritual, as well as the next three performed every week until the 21st day (called din shyak), are directed at the figure to ensure safe passage of the atman to the next world.

Pretty much every single ritual includes lighting butter lamps (see below).

Attendees are supposed to take butter for the bereaved family for the lamps, which I didn’t know either. The rituals are performed by monks who read the scriptures associated with death ritual. Part of the ritual also includes “feeding” the figure to help with the “journey.”

The fifth rite and ritual is performed on the 49th day, when the bereaved family invites community members to a meal while the monks again read the scriptures and light some more butter lamps.

The sixth and final rite and ritual is performed on the first-year anniversary. However, this one is not anywhere near as involved and elaborate. Butter lamps, again, are lit at home and at a monastery in the deceased’s memory and that’s it!

Growing up in a country with a Hindu majority and where Hindu culture, tradition and even outlook, is widely accepted as the norm, of course, I learned about some aspect of Hindu funeral rites, which of course are quite different from ours.

Hindu practice calls for, as far as I know, some of the male surviving members to shave (I think the whole body!), fast, even spend a number of days in isolation, give up certain kind of food items, and wear white clothes for a period of time. With us Tibetan-Buddhists, we don’t have to do any of that though we do engage in some outward display of mourning (such as not attending social functions for a period of time).

What do you think?