As a fourth grader, after having experienced one of the worst things that could happen to an elementary (primary) school kid (I was ostracized by my classmates), I went home for Dassain and Tihar school break to the news that the person for whom I was the center of his world, Khey (grandfather) Pani, had passed away in Mustang.

He had gone to sleep after a minor accident and had never woken up!

His passing was a big deal for me even then because he also meant a lot to me. As a matter of fact, the only reason I cried at night in bed, early on in my academic career at the residential (boarding) school, St. Xavier’s Godavari, was because I missed him.

And just as I did not understand how an argument between two friends ended up with me being ostracized by my classmates at school earlier that year, I also just did not understand how someone can go to sleep and not wake up at all! After all, I was just a child!

Years later, as an adult, I decide that my grandfather had met an untimely death.

At the time of his death, there had hardly been any medical facilities nor health workers in Upper Mustang. Had there been, my grandfather might have likely survived… to see me accomplish all that I wanted to and would have been even prouder of me than he had always been.

An incident last October while on vacation during one of the biggest Hindu festivals with a number of cousins reminded me of all that.

We were heading back to our accommodation, a river-bank camp site on the other side of the river, following a long evening of fun involving a lot of eating, drinking, singing and dancing. The walk involved a footpath including stone steps, a long suspension bridge and another set of longish stone steps lit by lights from our mobile phones!

One of my cousins slipped and fell down the first set of stone steps.

When I reached him, he was on his stomach. His older brother and a couple of others were trying to lift him.

Most of the rest of my company were pretty drunk. While everyone else had drunk hard liquor, the cousin’s older brother and I had drunk beer instead. So, while still a little buzzed, I was nowhere near as drunk as the rest. The cousin, for instance had fallen partly because he was pretty drunk himself.

My first instinct was to determine if he had sustained any injuries before pulling and lifting him etc.

But everyone was just set on doing just that and getting him, and themselves, across the bridge and to the tents to put him in bed and continue with the “festivities.” I did what I could to make them prop him up on his feet with care and concern.

Lifting him up, we noticed some blood on the ground. Examining his face, I noticed what looked like an injury under his right jaw. The mobile-phone lights revealed a blood streak that looked like a cut. (The blood on the ground, I later discovered had come from his mouth: he had chipped a tooth!)

At the camp, I ended up in a ridiculous argument with the rest over what to do with him.

I was trying to convince them to let me stay with him to keep him awake and monitor him. While I was insisting on that, pretty much everyone wanted me to “just leave him alone in peace to sleep it off.”

(The situation was yet another one of those really frustrating one that I have found myself in again and again in Nepal — one where people refuse to listen to reason! Yes, I am aware that they were all mostly drunk, but I have been in situations where sober Nepalis have also refused to listen to reason!)

That I needed to monitor him came from what I had decided, as an adult, about why my grandfather had never woken up from his sleep.

I still have a vivid memory of the exchange I had with my mom when she shared the news. We were next to one of the two windows in our bedroom.

My mother says, “Khey [Grandfather] Pani has died.”

I ask, “How?”

Mom says, “He wasn’t ill or anything. But he went to sleep with a headache and never woke up.”

My mother didn’t have any clue why he had died.

Inquiring further produced some more details.

It had been early evening when he had hit his head on the top door frame entering — on horseback — the house of a nechchang (hereditary family friend) he was visiting in another village in Upper Mustang. He had knocked his head so hard that he had sustained a headache. (Probably a pretty bad one.) After dinner he had gone to bed still complaining of the headache. The next morning, he just hadn’t woken up.

That at the time had appeared to me as much of a mystery as the argument between two classmates ending up with me being ostracized by my classmates at school!

Looking out the window into the blue autumn sky, I remember wondering, “How does someone not wake up after going to sleep?! Everyone does!”

At some point in my adulthood, outside of Nepal, I finally pieced together why: he had suffered a major concussion.

The concussion resulted in brain hemorrhage while he was asleep, which killed him! I don’t know for a fact that that’s what happened, but that was the most plausible explanation I came up with.

Lack of medical staff and/or facilities in the area had robbed me of the person who meant the most to me. Had there been at least a health post and/or a health worker, he might have visited the health post, or someone may have tracked down the health worker and asked to pay him a visit. The health worker could have monitored him etc. and he may have possibly survived.

(As for why my classmates ostracized me, not having anyone to turn to for answers but needing to know, I decided on my own that they did so because I was a Bhote.)

When I learned of his passing, as a young child in fourth grader I had no clue how his passing would affect me nor were I able to fathom the enormity of my loss (just as I had no clue how my being ostracized by my classmates would affect me later in my life). None of that even dawned on me.

As I grew up and as I passed milestone after milestone, I always wondered how amazing it would have been had grandfather Pani been around.

How proud he would have been. How I would have been able to share what I was doing, where I was going and why etc.

Like when I finished high school — as the first one from my entire extended family to do so! Like when I was offered the UWC Scholarship to go study in Italy — as the first one from my village and possibly even from the entire area of Upper Mustang to go study in Europe! Like when, after my two years in Italy, I got another scholarship to go to the US for further studies, just as I had dreamt of doing since a fifth grader, again as possibly also the first one from Upper Mustang!

Then starting my first career as an international teacher! Ok, granted, he might not have survived until then but…I always wondered what grandfather would have made of all that and how incredible it would have been to have him around to share all that with. After all, he had never even been to Kathmandu!

Growing up, I also learned that he was a highly accomplished and respected man in the village as well as in the region. Though he had no formal education, he was a medicine man, a veterinarian, a hunter, a leader with vast knowledge of the region and of our religion and spirituality — a mix of the indigenous religion of Bon and Buddhism.

It wasn’t until late into my teens, when I came across a void, that I realized who and what I had lost! I discovered I had had no male role models from my community who I could look up to, or who I could seek help or assistance from, or who I could share things with like about my hopes and dreams, about my friends and about my life etc. My grandfather, I was certain, could have been that person! But I digress…

Coming back to my cousin…his situation was different, I felt, because I was there.

I knew about concussions and what to do! I wasn’t certain that he had had a concussion. But, given the consequence of assuming the alternative and being wrong, the more sensible assumption to make was that he might have. He had obviously hit his right jaw on something. I assumed that he had hit it on a hard surface and that he might have sustained at least a slight concussion! That’s why I had insisted on monitoring him.

But a few cousins actually physically tried to prevent me from doing so by leading me away from the tent.

Luckily, my cousin’s older brother stepped in and convinced me to do what I wanted to and to ignore the others.

While he took care of the rest, I went into the tent, got him upright on his bed and just kept him awake by engaging him in a conversation. I kept asking him about the accident and how he was feeling and what he remembers etc. His jaw hurt but he didn’t have much of a headache. He told me how and why he fell. In the beginning, he just kept repeating the same things again and again, which was kind of amusing!

In case of a nasty concussion which might result in brain hemorrhage, one of the signs of its onset, as far as I know, is the slurring of speech. His speech pattern didn’t get worse over time! As a matter of fact, it got better…as he sobered up!

At some point in the night, I even managed to convince him to leave the tent and join the rest of the gang outside where they were still drinking and talking etc. We were all up until really late before we finally hit the sack. By that time, convinced that he didn’t have a concussion, I let him go to sleep.

This incident and the memories of how my grandfather passed away, highlighted, again, a number of things about Nepal and the people of the country which saddens me greatly.

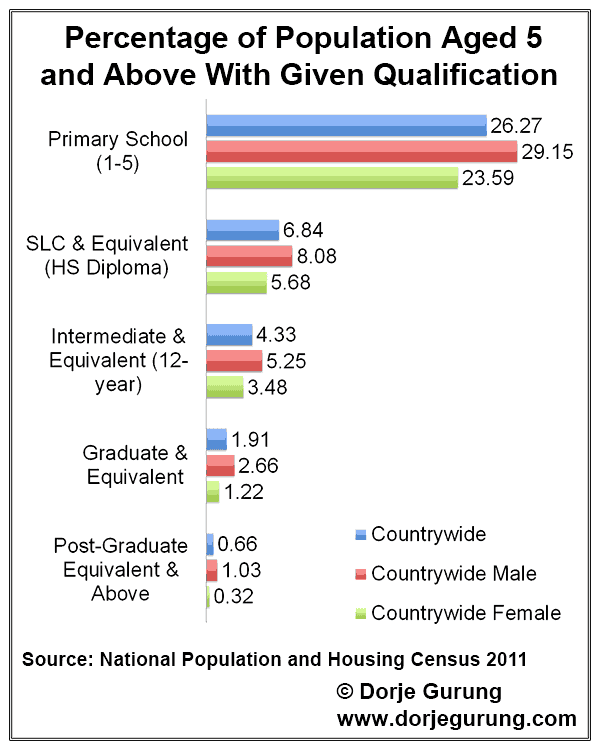

One of the most important, if not THE most important, is the low level of education of the population and how that is adversely affecting the way people think and act. According to the 2011 census report, less than 7% of the population aged 5 and above have 12 or more years of education (see image below)! Most of those cousins of mine, who I accompanied on that trip, don’t have 12 years of education.

Higher education available in the country is nothing to really rave about to begin with anyway!

Skills taught at academic institutions are mostly the ability to regurgitate and the ability to display some understanding. Critical thinking skills are mostly missing. Politics drives while education takes a back seat at public (government) institutions of higher education the majority of students attend. Universities, apparently, have had a longstanding practice of awarding Master’s Degrees, for example, on the basis of fake theses bought from local vendors.

Lacking in the ability to think critically and thereby question — such as superstitions and misguided beliefs [see references below added after the publication of the blog] — a majority of the population continue to behave the way their forefathers have done as well as follow their practices.

One such belief that has a stronghold on the population is fatalism!

Fatalism still rules the lives and dictates the behavior of many, including those of my cousins and other community members. Fatalism is responsible for a number of issues faced by the people of the country, including untimely deaths. What could otherwise may have been prevented with some knowledge, health and safety measures and precautions, as well as some basic facilities and personnel, is explained away by invoking fate. (Read Dor Bahadur Bista’s book Fatalism and Development: Nepal’s Struggle for Modernization for a more comprehensive treatment of the subject.)

Fate is invoked, for example, in explaining the circumstances and context of ones birth and thereby in justifying the caste system (click here and here for more on that). Fate also dictates when you die: you die when your time (kaal) comes and you can do nothing about it.

Belief in fate, in addition to lack of understanding of, or concern for, health and safety, I believe, is partly responsible for Nepalis taking a lot of unnecessary risks too. Such as driving recklessly. Such as not even thinking twice about, for example, wearing a helmet as — or putting one on — a pillion rider on a motorcycle or scooter. The number one killer of those between the ages of 20 and 30 in 2011 was traffic accidents. I am willing to bet that a significant percentage of those accidents involved motorcycles with pillion riders WITHOUT helmets!

That belief, in addition to lack of knowledge, I am pretty certain is also partly responsible for my cousins not thinking about, or agreeing to, my monitoring the injured cousin. The cousin who was most vocal about letting the injured cousin go to sleep, I know for a fact, believes in kaal, for instance. I am pretty certain the rest of my cousins, no different from him and many other Nepalis, believe in kaal too!

What I am also pretty certain about is that kaal was NOT entirely responsible for my grandfather’s untimely death in Upper Mustang of the seventies and eighties, a very very remote part of Nepal then. Lack of some basic knowledge and understanding about medicine as well as basic medical facilities and staff also contributed to his death.

I was glad to have made certain that kaal didn’t make an untimely visit to my cousin on the banks of Trishuli last October!

What do you think?

References

[Added after the publication of the blog post.]

- The Himalayan Times (Jan. 2018). Super blue blood moon eclipse on January 31. Some chairperson of a committee makes all kinds of recommendations on what one should not do during the eclipse without providing any objectively verifiable details for why.

- The Kathmandu Post (Jan. 2018). Woman dies in ‘menstruation hut’. “A 22-year-old woman who was banished to a hut nearby her house in Achham following the monthly period was found dead last night.”

- The New York Times (July 2017). Shunned During Her Period, Nepali Woman Dies of Snakebite. Superstition, obviously, is the basis for the practice.

- News24Nepal (Feb. 2018). आमा-बुबाको यस्तो सानो गल्तिले नै “तेस्रो लिङ्गी ” जन्मिनछन्. (“These simple mistakes by parents result in the birth of an Intersex child.”) The article lists six mistakes that the mother might make during the first trimester of the pregnancy which five of which are outrageous. I have translated them in the blog post Intersex, Women, Men and Nepal. The article provides NO scientific basis for their arguments!