The Roots of Stagnation

While a poorly, lowly, and selectively educated population is, to me, the biggest hurdle to Nepal making cultural, social, economic, and political progress, there is also a deeper cause. The casteist history of Nepal, involving deeply entrenched structural discrimination and systemic casteism, is also a major reason for this failure. Not surprisingly, the public in Nepal—whether individuals or the media—does not dwell much on that fact, shaped and controlled as they are by the attitudes, mentalities, cultures, systems, and institutions of, for, and by the hill so-called ‘high-caste’ Hindu men.

The structural discrimination and systemic casteism Nepalis experience today are hallmarks of pretty much every system and structure of importance in the country. They are a legacy of attitudes, mentalities, ideologies, beliefs, and practices—conscious or unconscious—sown by Prithvi Narayan Shah, the ruler credited with the creation of the country of Nepal. This is now known or labeled as Bahunbaad, Bahunvada, or Brahmanism in English.

In his article Bahunvada: Myth or Reality?, Kamal P. Malla describes how this began:

“After 25 years of persevering belligerence, Prithvi Narayan Shah conquered the three cities of the Kathmandu Valley in 1769. One year later, on 23 March, he shifted his capital to newly occupied Kathmandu. With his court came his kinsmen, retinue, priests and soldiers — the new aristocracy of the hill region — to settle permanently in Kathmandu. They symbolised what Nepal’s leading economic historian Mahesh C. Regmi calls ‘a shift of political and economic power.’ Among them were the thar-ghar, the chosen and select families of hill Brahmins such as Aryal, Khanal, Pandey and Panta, who were rewarded with the best lands and houses in the Valley as their jagirs in return for their services to the Gorkhali court in war and peace. Thus begins the success story of the parbate Bahuns, the Brahmins from the hills.”

Institutionalizing Discrimination

To many in the country, this history has amounted to internal colonization. Successive rulers and governments of the “high-caste” hill Hindus so institutionalized structural discrimination and systemic casteism that these forces were deeply entrenched in nearly all major systems and institutions by the time the people rose up to topple the autocratic Shah regime in the 1990 Jana Andolan (People’s Revolution), almost 250 years later.

Not surprisingly, all that the revolution did was pave the way for a new group of the ruling caste—the hill so-called “high-caste” Hindus—to rule. After all, the rulers until then had successfully provided the population with a very poor and selective education.

Case Study: The Nepal Army

Since 1990, the cultural, social, economic, and political systems of importance in Nepal have not significantly changed in kind or composition. This legacy of exclusion is visible in pretty much every key institution of the government, including that which is tasked with national security: the Nepal Army.

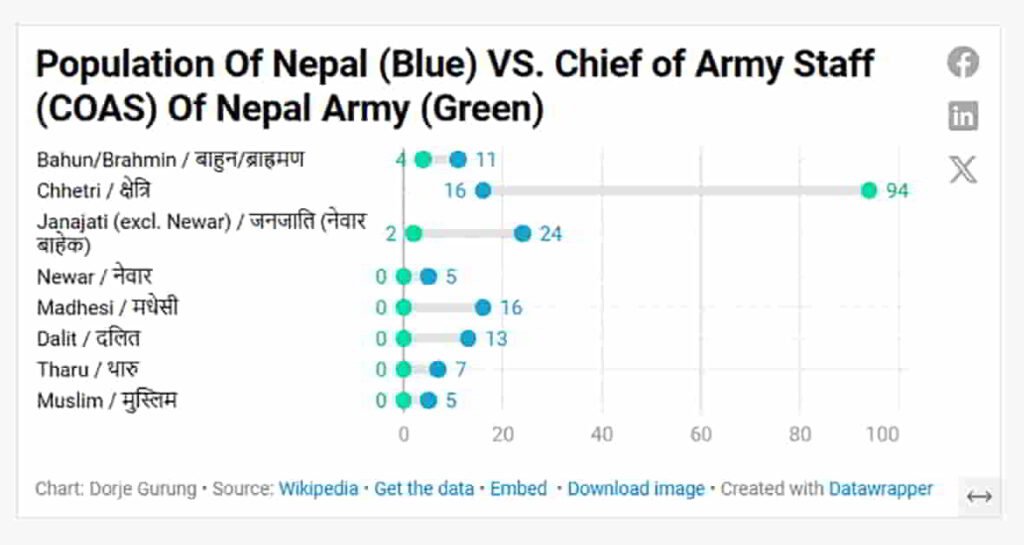

To begin with, who has been the Chief of Army Staff (COAS) of Nepal, and how do they compare with the population of the country? (See chart below).

The Nepal Army has eight divisions in total, each headed by a General Officer Commanding (GOC). Who have been the GOCs, and how do they compare with the general population? (See chart below.)

The Bahun/Brahmin and Chhetri make up the hill so-called high caste Hindus. As you can see, while they represent about 30% of the population, they have pretty much have had a complete monopoly on the highest posts in the Army.

Furthermore, what about the gender makeup of the COAS and GOC? In both cases, 100% are men.

In the patriarchal, sexist, and casteist society of Nepal, there is no dearth of people who will tell you that Chhetri men—the “Warrior caste”—are born to perform these duties. They parrot the teachings of Hindu culture and mythologies steeped in patriarchy and casteism. How many belonging to the ruling caste concede that these structures are also about caste hegemony and supremacy?

Hindu mythologies are also built upon these themes, yet they fail to explicitly teach the population about the darker side of stories like those of Eklavya and Dronacharya. In the story, the hill so-called high-caste Hindu teacher, Dronacharya, deviously attempts to ensure a highly skilled, self-taught low-caste archer, Eklavya, is unable to pursue his talent in order to protect his most favored and skilled disciple, Arjuna, a high-caste prince. This ancient narrative of suppression mirrors the modern exclusion we see in our most vital institutions today.

What do you think?

NB. The charts on which the data in this blog post appear were also shared in this May 2025 X thread. I got help from Google’s AI Gemini composing this blog post.