Being pretty completely acculturated as I had been in and by Nepali society while growing up, only as a post-secondary student and professional abroad did I question seriously and deeply the mostly Hindu-mythology-based beliefs, practices, values, and world view inculcated in me by Nepali society, culture, and people, and what they represented. The story of Eklavya and Dronacharya is one such mythology.

My questioning have led me to conclude that the story is more of caste supremacy than model discipleship.

The Story: A Synopsis

The story goes that Eklavya desires to master archery. What’s more, he wants to learn it from the best there is: Dronacharya. Unluckily for him, Drona refuses to be his coach.

So undeterred and resolute in his determination to master it under Drona’s tutelege is Eklavya that, he retreats into a forest, erects a statue of Drona, treats the statue as his coach, showers his devotion to it, and basically…teaches it to himself. He develops into a highly skilled archer.

When Drona hears of Eklavya and his skills, from an extremely jealous Prince Arjuna, he seeks out the young man. On discovering Eklavya to indeed be a master archer, even more skilled than Arjuna — his favorite and most skilled of all his students — Drona connives to bring him down.

Drona asks Eklavya if he is ready and willing to fulfill the duty of the devoted student that he clearly has been and for becoming such a master archer under “his coaching.” Will he present the necessary “Guru dakchhina” (“gift for the coach/teacher”) owed to him? Apparently, “Guru dakchhina” was a highly prevalent practice at the time.

Eklavaya promises to give anything Drona asks for.

The teacher demands Eklavya’s right hand thumb to prevent him from practicing archery ever. The latter obligingly cuts his thumb and presents it to Drona. (The top left corner of the header image depicts that act.)

From then on, Eklavya, so the mythology goes, has been celebrated as the model disciple. He was the model student all of us in Nepal were taught to emulate, to aspire to become like!

Two Versions of the Story

This version of the story lays out clearly the interpretation we were taught but now I find…abhorrent. The narration even goes as far as to imply that Eklavya’s fame throughout the world and history as the “epitome of discipleship” was a just “reward” for his act.

And who do we have to thank for all that? Drona! In other words, what the Guru (teacher) — the venerable, the knowledgeable, and wise Brahman teacher, Drona — did, in his infinite wisdom, was really for Eklavya’s own good in the long-run, even if personally painful at the time, argues this version! That is, we are supposed to celebrate Eklavya being duped, handicapped for life, and prevented from getting anywhere close to realizing his human potential.

There’s more. The retelling of the mythology concludes with a long quote by some Ravi Shankar: “[Drona’s] duty was to maintain the law of the land: You cannot have anyone much better than the [Kshatriya] prince [Arjuna].”

To begin with, the implicit assumption is that the “law of the land” is about exalting the Brahmans and the Kshatriyas and their ways is THE way. The other assumption is that the land couldn’t and shouldn’t have a non-Kshatriya master archer, certainly not one better than the best Kshatriya.

Of course, that’s consistent with the belief that having one would have been an insult to ALL the Kshatriyas, the warrior caste! The social and political systems of the time called for ensuring that didn’t happen. Drona just played his part in making sure of that.

Needless to say, those arguments say so much more about the mindset of the author(s) — likely also Brahmans!

This version of the story, on the other hand, does a better job as it identifies Eklavya as a Shudra, which is extremely important to the caste supremacy angle of the story.

The Hindu social system divides people into four major castes. Here’s a reproduction of the description of Shudra as found in the Britanica.

Shudra, also spelled Sudra, Sanskrit Śūdra, the fourth and lowest of the traditional varnas, or social classes, of India, traditionally artisans and labourers. The term does not appear in the earliest Vedic literature. Unlike the members of the three dvija (“twice-born”) varnas—Brahmans (priests and teachers), Kshatriya (nobles and warriors), and Vaishya (merchants)—Shudras are not permitted to perform the upanayana, the initiatory rite into the study of the Vedas (earliest sacred literature of India).

Were the story ONLY about discipleship, it could have been conveyed without a Shudra character and without all the hoopla around Arjuna, his jealousy, and Eklavya not being admitted to the Gurukul, a school for only Brahmans and Kshatriyas, etc.

The Subtle But Not so Subtle Subtexts

One of the more important implicit lessons the mythology imparts, or rather reinforces, is how professions are based on birth — martial skills, for instance, are reserved for Kshatriyas, and knowledge, education, and teaching are the domains of Brahmans.

In other word, birth is an end, NOT a beginning.

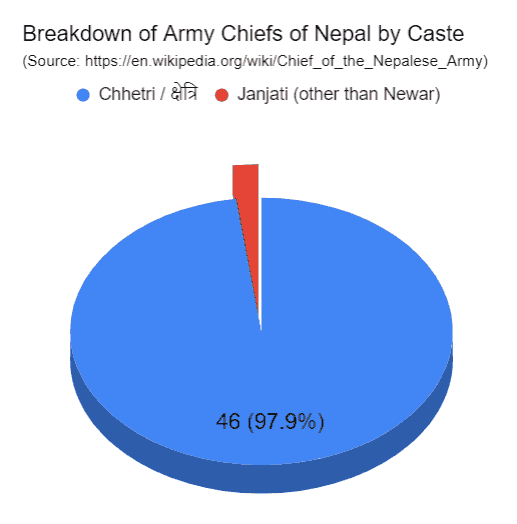

Viewed from the perspective of modern Nepal, the equivalent of reserving the study of martial skills for the Kshatriyas (in Nepali, Chhetri) you can see in the way Nepal Army has been and continues to be under their exclusive control. We have had 47 Chief of Army, for example, but only one has been a non-Chhetri (see image below).

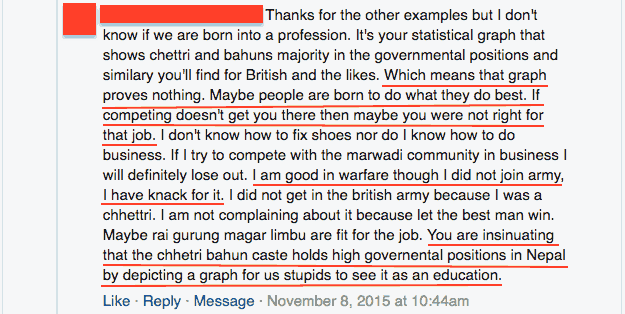

I wouldn’t be surprised if the following Chhetri man is NOT the only one in Nepal who believes in “[Chhetris] being good in warfare” and having a “knack for it” because of…his — yes HIS — random birth caste, even in spite of not having engaged in it at all! (Privilege can be blinding, especially when mythologies and power structures back you up!)

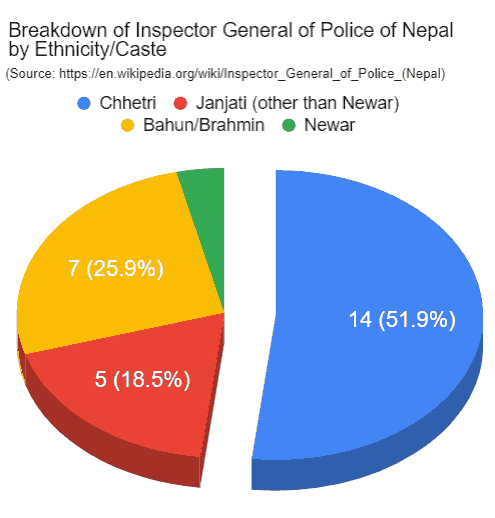

Even Nepal Police has been under their control. Of the 27 Inspector General of Police, 14, over 50%, have been Chhetri, and 7, over 25%, have been Bahun (Brahman). So, over 75% have been hill so-called high castes.

According to the 2011 Census Report, the hill so-called high caste Hindus make up only 31% of the population.

The story also serves to impart a second and more important but insidious idea of the supremacy of the so-called high castes. To that end, the story is a warning and a threat to everyone else to not challenge or question that.

Viewed from the perspective of modern Nepal, the story is a warning to the non-high caste Hindus to remain in “one’s taha (तह)” (“one’s place”) and help contribute to and maintain the God-given “social order.” If you punch above your caste-prescribed weight, as it were, they will put the offender “in their place” (“तह लगाउछ”), possibly even by employing some extreme and/or devious measures.

If you care to look, you can find examples upon examples of such measures throughout the modern history of Nepal.

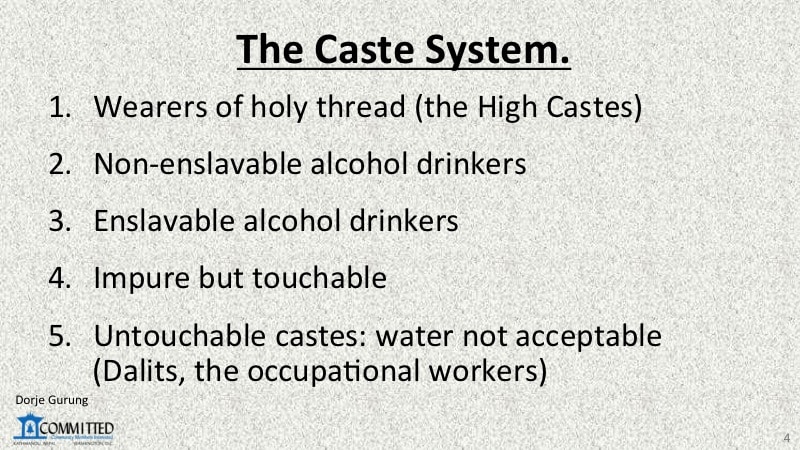

The feudal and oligarchic Rana (Kshatriya) rulers of Nepal, for example, put in place just such a measure in the country’s 1854 Muluki Ain (“Law of the Land”): they legalized the caste system. The system slotted the Brahmans and the Kshatriyas (“the wearers of the holy thread”) at the top of the pecking order (see image below).

In Nepal’s case, the Shudras are the Untouchable Castes, the fifth one. Please also note, the third caste consists of those who are “enslavable.”

Additionally, they included provisions for caste-based punishments for the same crime: the lower the caste of the perpetrator, the more severe the punishment.

The Rana rulers, for instance, condemned to death four of the five members of the treasonous Nepal Prajha Parishad but sentenced the fifth one to life in prison. They spared Tanka Prasad Acharya’s life because their laws forbade even the State from killing a Brahman.

Another oppressive and suppressive provision was making the cow sacred and its killing, in some cases, worse than taking the life of another human being. That victimized the mountain people and many hill tribes who traditionally ate what, to Hindus, passed for beef. That law also unjustly victimized and continues to terrorize a subset of Dalits whose traditional profession, for lack of options and opportunities, involved working with dead cattle.

As if all that wasn’t oppressive and prohibitive enough, the “Law of the Land” consisted of provisions that deliberately and specifically promoted the hill so-called high caste Hindus and marginalized everyone else. Policies allowed redistribution of land traditionally under the control of indigenous communities to the so-called high castes. Dalits were legally prohibited from owning land.

Thus, Nepal’s “Law of the Land” of 1854 and social and traditional practices promoted and fostered the belief that anyone doing or becoming — or even aspiring to — something prohibited by the caste-based system is “unbecoming” or “unsuitable” or “inappropriate.” We have a Nepali word to describe just that: “aaukat” (औकात). That is, what one attempts to acquire, be, do, or even what one says must be congruent with, or match one’s, “aaukat“: what the casteist social system permits as per the caste one belongs.

To be sure, measures to ensure caste supremacy were not limited to just Laws and official State systems and institutions. State and other actors also enforced informal “policies” to that end.

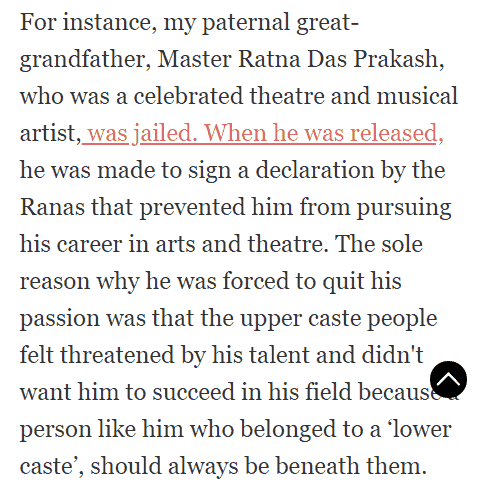

Here’s an example of a modern day Ekalavya (Master Ratna Das Prakash, a Newar) and Dronacharya (the Rana, Kshatriya, rulers).

The hundred-and-four-year feudal Rana rule ended in 1951. The 1854 “Law of the Land” was partially revised only in 1963, by which time the damage had already been done; the legacy lives on still today, in the 21st century!

In September 1986, the autocratic Shah monarch (Kshatriyas), attempted to have Padam Thakurathi, a journalist, assassinated for challenging, in his writing, the dominant political system of, by, and for the so-called high caste Hindus.

In 1988, Gopal Gurung was jailed by the same autocrat for his book Hidden Facts in Nepali Politics.

Average Joes and Janes in the country also contribute to the maintenance of the supremacy of the high castes. A recent and one of the most heinous of acts, whose foundation lies in the belief in “aaukat,” took place in May 2020. A mob of 50-60 villagers lynched six Dalit males in Rukum. Their “crime”? One of the males daring to love someone of a higher caste in their village.

According to Haatemalo Collective, 2020 saw over 200% increase in assault and murder of Dalits from 2019. That’s a 3-fold increase in crime against the MOST vulnerable social group in the country in the midst of the unprecedented times of the coronavirus pandemic! Think about that for a moment! That happened as the entire world has been gripped with and suffering from the coronavirus pandemic, and the very poor all over the world including in Nepal, of whom disproportionately high percentage are Dalits, were disproportionately suffering because of that both directly and indirectly!

Female Dalits in Nepal suffer more than others too! Disproportionately high percentage of female victims of rape, both adults and minors, are Dalits.

Not leaving anything to chance, even Nepali labels for people of the country are imbued with negative connotations and are demeaning — symbolizing their lowly “place in society” and representing their lowly “aaukat.” The pejorative label Bhote (literally, “Tibetan”), for example, is used liberally to refer to not only those of us from the mountains but also to almost all Nepalis of Mongolian stock. That is, to even some hill tribes, such as the Tamangs. Madhesi (literally, “one from the plains”) is another slur — it being used for the indigenous population of the Southern Plains. It might not surprise you to know that Nepali, or Khas-kura, is the mother tongue of the so-called high castes and the ONLY official language of the country.

What of the impact of the mythology and the Muluki Ain on the psyche of the so-called low castes? What of the impact of another one of their legacies: people following or enforcing, within their communities for the entire modern history of Nepal, social dictates that the “Law of the Land” indirectly fostered and promoted? There can be no doubt that they must have inflicted immense generational trauma on the marginalized. (What’s generational trauma to most Nepalis anyway?!) Worse, all of that was deliberate and intentional.

How much terror and trauma were inflicted in for example the Tamangs and the Tharus, both belonging to the “enslavable alcohol drinkers” caste, virtually enslaved and exploited mercilessly by the ruling castes? Even to this day, Tamang girls are exploited for sex work, something started by the Rana rulers, for example. As for the Tharus, only this century adults were liberated from their virtual slavery as Kamaiya and their girl-children as Kamlaris.

I am sure so-called high caste Hindu apologists will likely argue that the treatment meted out to Eklavya and the policies surrounding the Tamangs was “strategic”!

Regardless, how much terror and trauma are STILL being inflicted on the Dalits? Even worse than the fact that all of that was deliberate is the fact that we will never know because, as far as I can tell, there will never be any accounting or reckoning of any of that.

Injustice inflicts the deepest and gravest of wounds.

But you won’t know that unless you have suffered from a grave injustice. And if you haven’t, the best thing you can do is to empathize with those who have. All humans, and even apes, studies have shown, have the capacity for empathy.

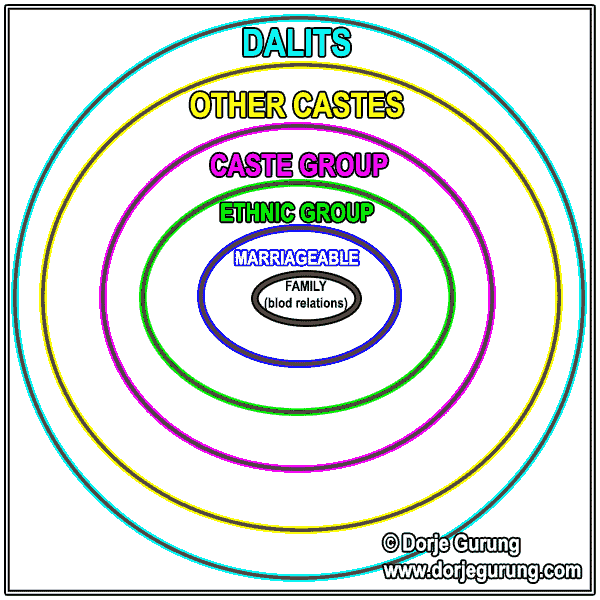

Sadly, one of the other legacies of the caste system is that Nepalis really struggle to empathize with others, including victims of injustice, unless they are from within their circles of concern — notably a family member or closely related, or, possibly, a member of their ethnic group. Forget empathize with people outside of the three concentric circles (see image). Least of all, with the Dalits.

So, to conclude, the legacy of the Eklavya-Drona mythology — and many other similar tales furthering caste supremacy and other regressive caste-based beliefs and practices they dictate, espouse, and further — is the belief that you are born into a caste consistent with the way one has led one’s past lives (Karma), and therefore everything life gives — or throws at — you are “deserved.” We don’t have a dearth of Hindus in the Indian Subcontinent whose belief in that is so strong that it’s as if like it comes coded in our DNA!

I wouldn’t be surprised if you are able to make additional arguments for why the authors of the story made sure to paint Drona and Arjuna (symbols of the high castes in the mythology), as being so COMPLETELY against Eklavya (a symbol of other castes) acquiring archery skills, a skill at the time symbolizing their power, their “taha” (तह), their “aaukat” (औकात), and taking the action that they did…and their like continuing to do so even in the 21st century.

What do you think?