Let’s start this fourth blog post in the series on the 2022 elections by taking stock of the grim reality we’ve uncovered so far.

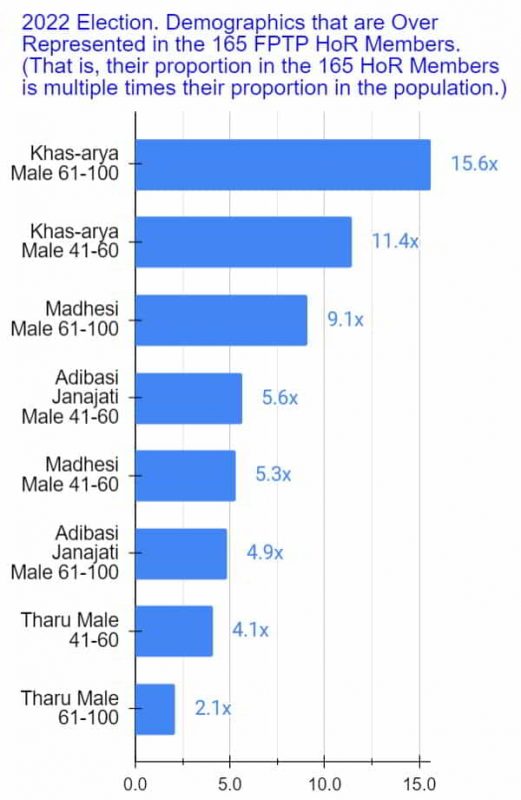

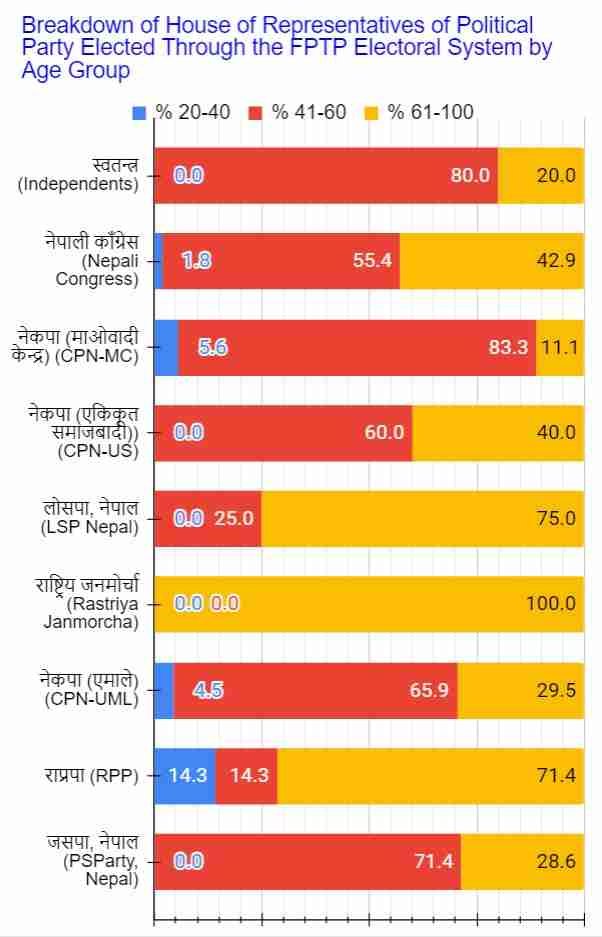

The first post revealed how old Khas-Arya men (defined as those above 60 years of age) enjoy the highest success rate of any demographic in the country. The second demonstrated how some results can be explained by statistics, while others are “statistical anomalies” that defy logic. By the third post, the conclusion was inescapable: relative to their actual population size, older Khas-Arya men are the most disproportionately overrepresented group among the 165 members elected through the FPTP system.

The rest of Nepal? We are either underrepresented or not represented at all.

But make no mistake: this is not because voters have a biological preference for older Khas-Arya men. The reason is a systemic failure I have repeated throughout this series:

“Overall, however, those results are all consequences of the ‘democratic’ process of election in Nepal–the official and unofficial systems that create and enforce the rules and regulations of the process, the political institutions involved, and, most importantly, who mostly have had and continue to have the power in those institutions to make the critical decisions that directly or indirectly affect, or rather pre-determine, the outcomes of such elections, and why.”

The people creating and implementing these rules are the same people benefiting from them: mostly older Khas-Arya male politicians and bureaucrats.

The Mechanics of the “Fix”

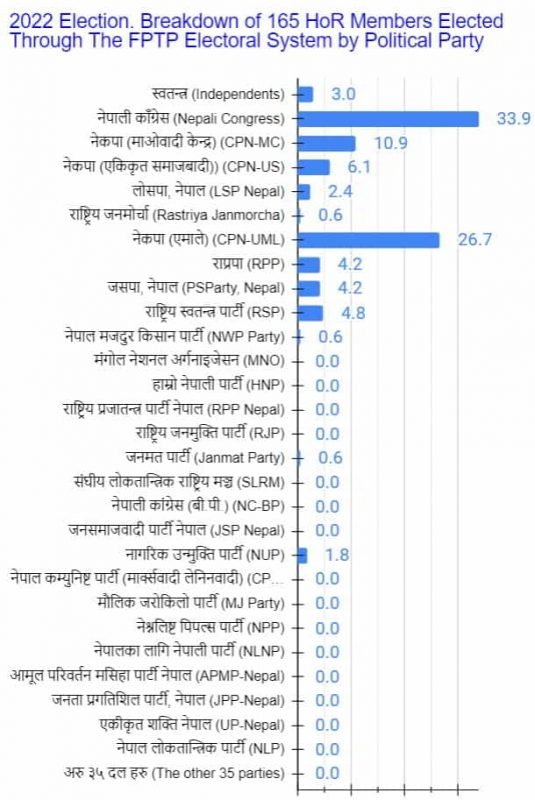

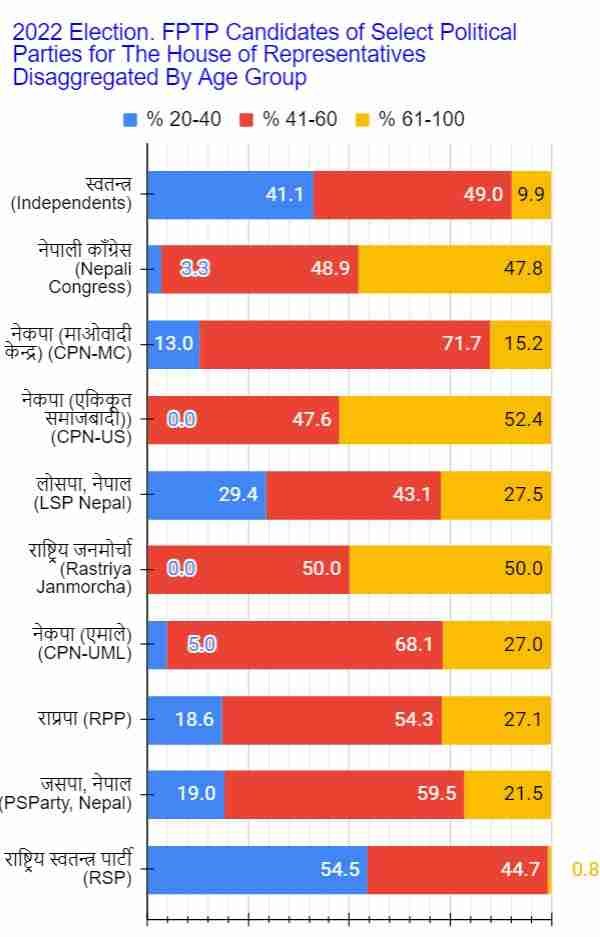

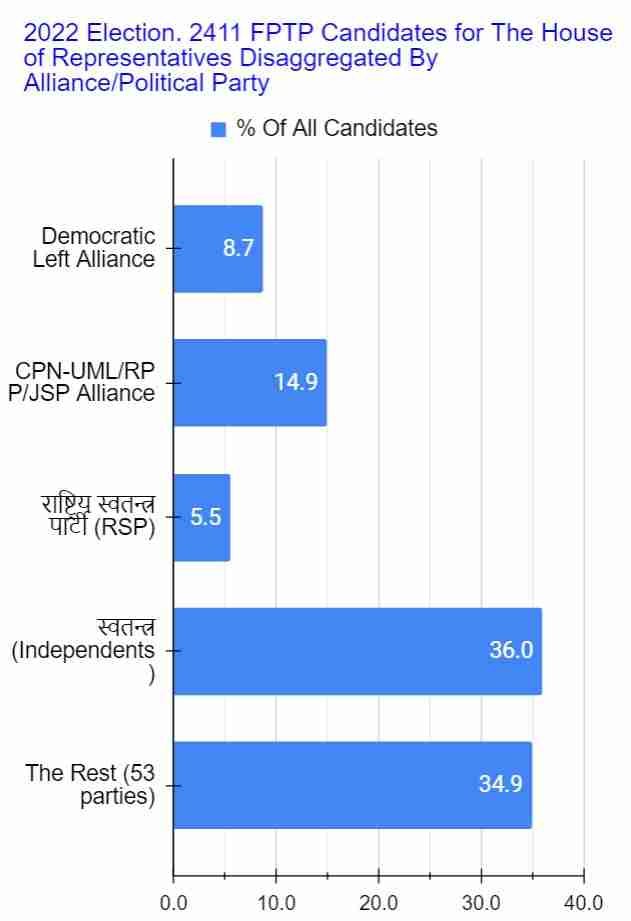

Let’s look at the data. If we look at the candidate pool by party (filtering for those with more than 10 candidates), a startling trend emerges:

- Nepali Congress: 3.7% of the total candidate pool

- CPN (UML): 5.8%

- CPN (MC): 1.9%

- RPP: 5.8%

- CPN-US: 0.9%

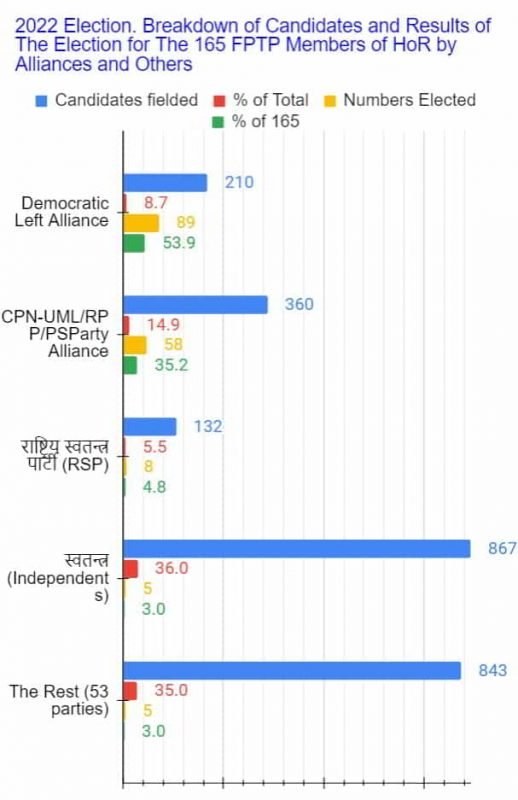

Compare this to the RSP, a party formed just before the election, which fielded 5.5% of the candidates—more than the Nepali Congress and CPN-MC combined!

The Success Gap

Now, look at who actually got into the House. Despite fielding only 3.7% of the candidates, the Nepali Congress captured 33.9% of the seats. Their success rate was 9.1 times higher than their candidate proportion.

Similarly, CPN (MC), CPN (US), Rastriya Janmorcha, CPN (UML), PSP-N, and NUP all saw disproportionately high success. How do these parties—specifically the “big three”—ensure such victories that defy statistics?

They rig the system.

While 62 political parties and a wave of independent candidates contested the election, the old-guard parties “stacked” their candidates and formed strategic alliances to manufacture the results they wanted:

- The Democratic Left Alliance: Nepali Congress, CPN-MC, CPN-US, LSP Nepal, and Rastriya Janmorcha.

- The Opposition Alliance: CPN-UML, RPP, and PSP-N.

These alliances functioned as a single political entity. They ensured they did not field more than one candidate in the same constituency, effectively locking out competition. This is made easy by a deliberate loophole: in Nepal, the party and the candidate—not the local community—decide where a candidate contests from. This allows party elites to parachute into “safe” seats guaranteed by their alliance partners. Furthermore, the “ticket” for a constituency is decided by senior leaders… for a price.

The Result: A Manufactured Outcome

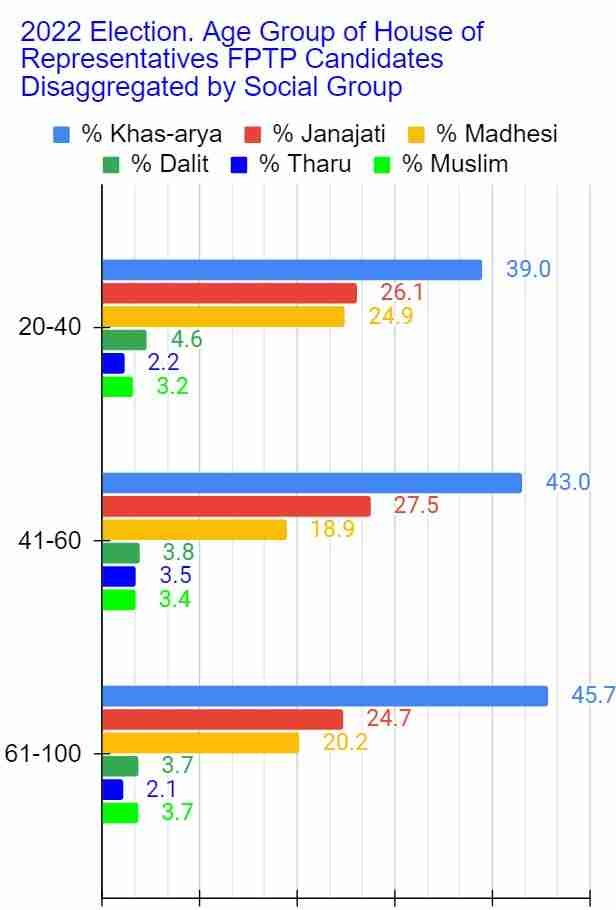

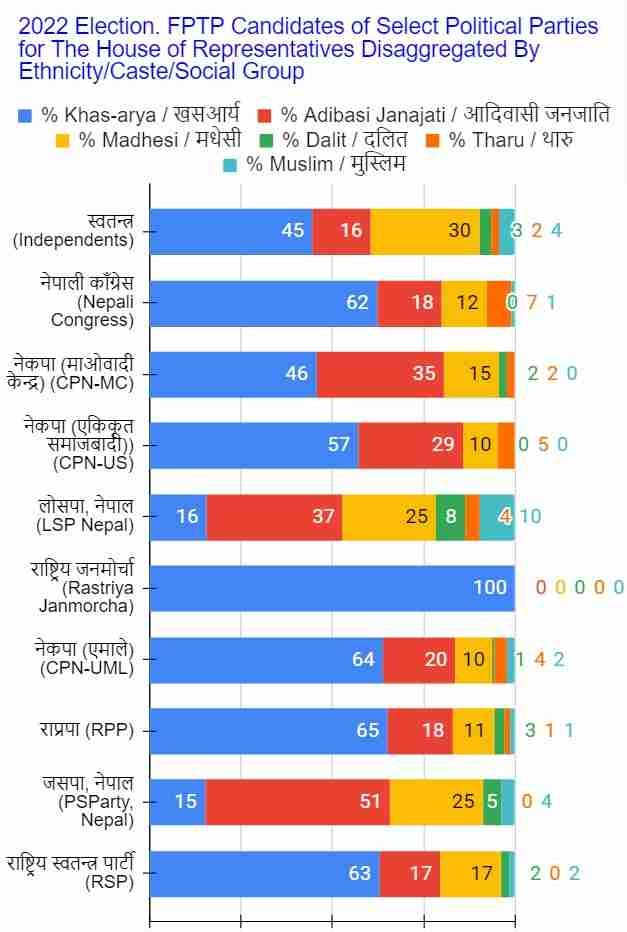

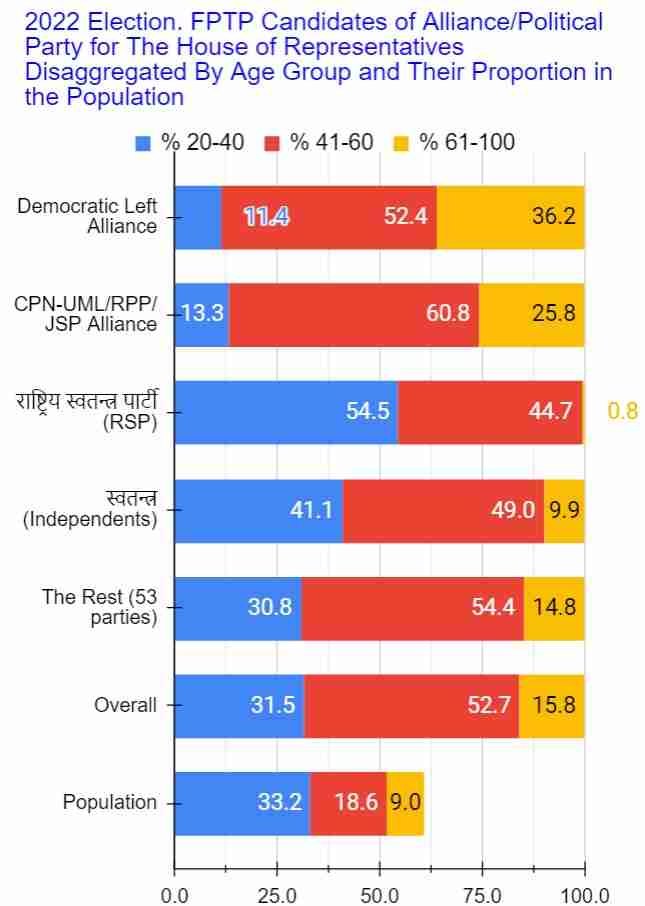

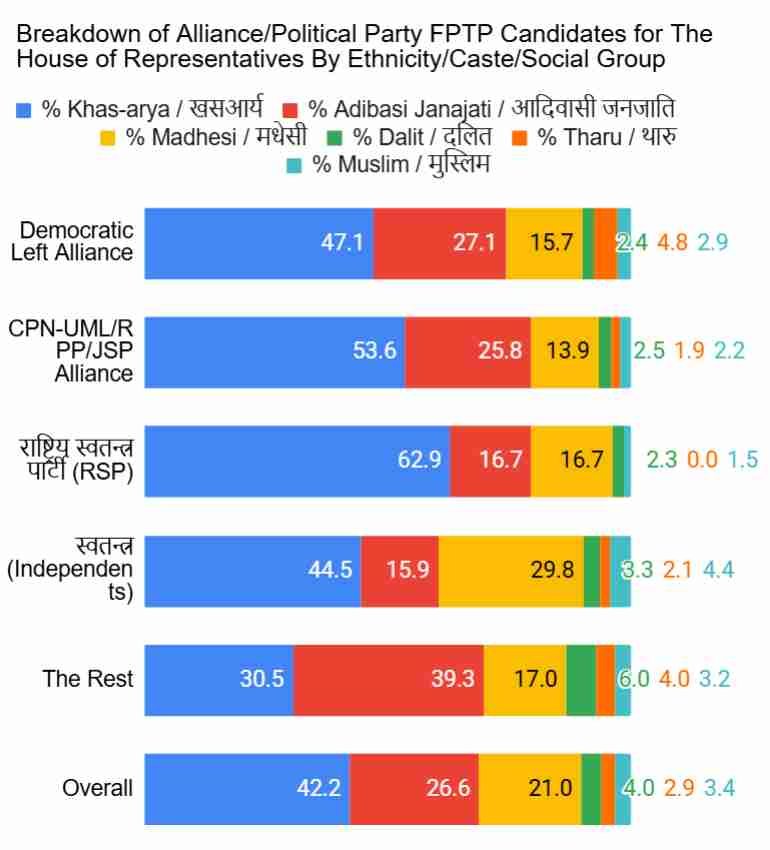

When we disaggregate the candidates by age and social group, the “fix” becomes visible. Every big political party fielded a disproportionately high percentage of old Khas-Arya candidates.

Their alliances further concentrated this power. RSP is no longer the party with the highest number of candidates when the alliances are viewed as single blocks.

A breakdown of these alliance candidates shows a predictable trend: a disproportionately high percentage are elderly and Khas-Arya.

The strategy worked perfectly. Parties within these alliances and their elderly candidates performed significantly better than those outside of them. The Nepali Congress and CPN-UML were the biggest beneficiaries, securing power while fielding a relatively tiny number of candidates.

The rules allow this, but we must remember: those rules were created, implemented, and enforced by the very people they benefit. These rules serve old Khas-Arya males with power—the decision-makers themselves.

Conclusion

The evidence is in the numbers, but the intent is in the rules. We are not seeing the “will of the people”; we are seeing a carefully choreographed preservation of the status quo. There is still much more to elections in Nepal than what I have exposed here, but I hope a few of the “how” and the “why” have become clear.

What do you think?

PS. I got Gemini AI’s help composing this blog post.