A repressive, oppressive, and suppressive regime, bent on demonstrating, consolidating, and abusing their power wields tools to that end. Such tools end up representing the regime, especially after they fall. While some such representations or symbols might be quite innocuous, some others may come to symbolize its brutality and suffering inflicted on even a large percentage of the population for generations. They may thus be responsible for generational trauma afflicting members of the population.

In Nepal many such symbols of the past regimes — the autocratic Shah rulers and the feudal Rana oligarchs — exist. The rulers and their courtiers belonged to one caste: the hill so-called High Caste Hindu. For that reason, for example, the regimes were horrendously casteist and, as if that wasn’t bad enough, they were also brutal in some other instances, areas, and ways. So, most of those symbols, as far as the rest of the population is concerned, are associated with — justified or not, right or wrong, more or less — the so-called High Caste.

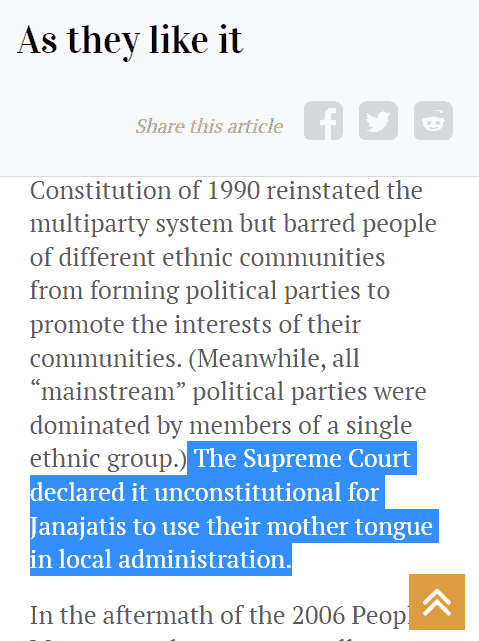

Among those symbols is Khas-kura (Nepali language), their language — still the ONLY official language of the country. Even in 1990, following a bloody revolution overthrowing the authoritarian Shah regime, the Supreme Court declared the use of mother tongue by indigenous population in local administrations “unconstitutional” (see below).

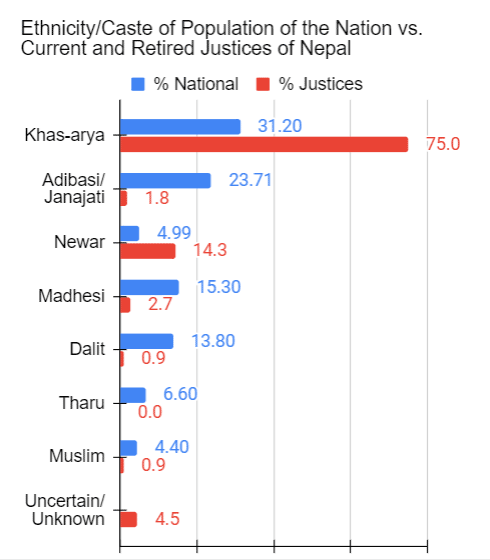

Why wouldn’t they? The Supreme Court was likely disproportionately highly filled by the hill so-called High Caste Hindus, also referred to as the Khas-aryas. See below for a breakdown of the 2021 and retired Supreme Court justices and their comparison with the breakdown of the population of the country. At 75%, their representation is more than twice that of their proportion in the population! That is, they essentially have had a monopoly over it.

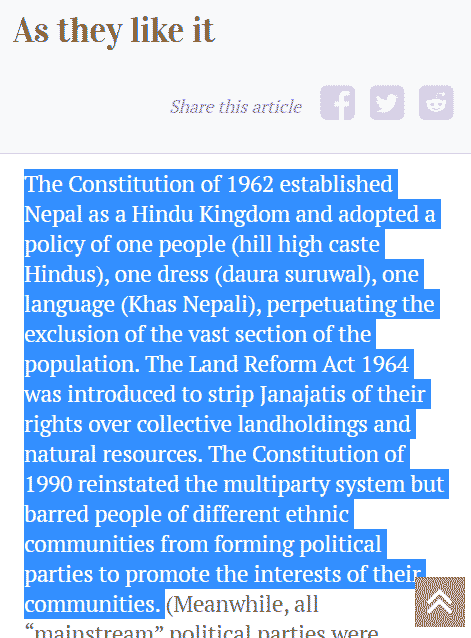

Other such symbols are the religion Hinduism itself, daura suruwal (official uniform of males but the traditional attire of hill so-called High Caste Hindu males), and the Dhaka topi (Nepali cap) etc. Why? Here is but just one reason (see below).

Yet another such symbol is the biggest (Hindu) national festival: Dassain. The festival, naturally, has some dark history that many Nepalis don’t know about or refuse to acknowledge.

In a two-part blog series, I shall be dwelling on, one, the details of that history and, two, how Nepalis on Twitter display their lack of knowledge and understanding of that history.

To talk about the history, I shall be using materials from the article लिम्बू र किराँतीहरूलाई यसरी बाध्य पारियो दसैं मनाउन (This is How Limbus and Kiraties Were Forced to Celebrate Dassain) published by Setopati last year. The article basically is a reproduction of parts of a conversation with Bhagiraj Ingnam, an authority on Limbuwan history and winner of the Literary Prize Madan Puraskar. Limbus are an indigenous population native to the North-eastern parts of Nepal.

What follows are translations and explication of select bits from the article.

Ignam relates how it’s been three years since his immediate family has stopped celebrating Dassain. His siblings, however, stopped celebrating it almost 35 years ago! When he did finally make the decision, he gathered his family together and told them “Dassain is not a good festival.”

According to the highlighted bit below, “[Limbus and the Kirati community] started celebrating Dassain around two hundred and fifty years ago under pressure from the State [of Nepal]. Nowadays, they are abandoning the practice saying, ‘It’s NOT our festival.'”

“Before Prithvi Narayan Shah’s expansion of his kingdom of Gorkha, Limbuwan was a Sen kingdom. Only a few Limbus had converted to Hinduism under pressure from the State; they would celebrate Dassain.”

But, it didn’t take long before the population in the area agreed to — and did — celebrate Dassain.

The bit reproduced below says, “The Limbus, during Dassain, were required to make sacrifices of goats and water buffaloes as per the ordinances of the State. Following that, to show that they had done so, they had to dip their hand in the blood of the animal and place a red-blood palm print on the outside wall of the house.

“The central Government sent police officers to check that the Limbus had indeed celebrated the festival in the way they were supposed to. Houses with the bloody prints were assumed to have done so. Those without were declared as having violated the State’s edict and punished.”

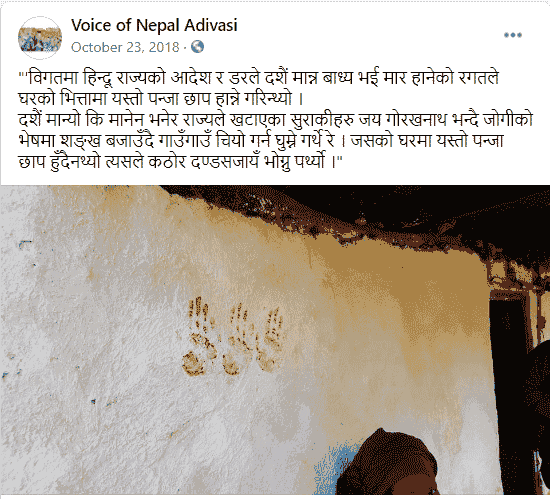

The image below found on the Voice of Nepal Adivasi Facebook Page depicts a house with the bloody palm print. The post says how the police officers, “inspectors,” would “come disguised as ascetics, blowing a conch.” It adds, “Those missing the prints on the their homes received severe punishments.”

What were some of the punishments? According to Ingman (see below), “They ranged from confiscation of traditional communal land (Kipat) to that of being stripped of titles and positions, such as Subba — heads of local administration. Fear, Ingnam explained, forced Limbus to celebrate Dassain.

“During the reign of Janga Bahadur [the Prime Minister who established the 104 year-long feudal Rana oligarchy] two were condemned to death for not celebrating Dassain, according to him. ‘The Aathpariya living around the periphery of Dhankuta don’t celebrate Dassain. Two priests called Na Ramlihang and Ridma were hanged for the offense.'”

Ingman goes on to mention other districts where the indigenous population celebrated their traditional festivals instead of Dassain. However, people from those districts who had migrated to the cities did.

One of the districts mentioned is Mustang, the district I am from. And yes, he is right about us Mustangis in the cities — including my own family — kind of celebrating it way back in the days of the Shah autocrats. That, however, was only one of the number of different things we did when I was a child in order to demonstrate to the society at large that we were indeed Nepali and for Nepal! I don’t know when my family stopped celebrating it but in the last 9 years I have been back in the country, we never have.

The historian also mentioned how, while Dassain celebrations were just making inroads in many parts of Nepal, “Limbus and members of the Kirat community have been abandoning the practice in protest.”

Having said all that it’s likely that the State of Nepal coerced other traditionally non-Hindu indigenous populations around the country — such as the Rais, Gurungs, and Magars to name a few — to celebrate Dassain and also adopt some additional Hindu beliefs and practices etc.

At the end of the article, something Ingnam mentioned resonated with me. He believes Tihar should replace Dassain as the biggest festival of Nepal.

He argues, in the text below, that Tihar is celebrated by more Nepalis than Dassain — from the mountain people to those in the plains in the South!

BUT, sadly, under a tweet of this article by Setopati, quite a number of Nepalis have willingly but unwittingly exposed their ignorance and arrogance. Again, let me remind you, the article is based on a conversation with Bhagiraj Ingnam, an authority on the subject! And yet, Nepali Twitter users attacked it.

Having said that, I have noticed that it’s NOT unusual to see Nepalis expressing their displeasure at fellow Nepalis protesting against Dassain at and around the time it is celebrated — in the Fall of every year. How they have done that and what they have been saying however shall be the subject of the second and final blog post in the series.

What do you think?

* * * * * * * *

Related Reading Materials

- If protests against Dassain hurt your sentiments…

- Dassain: Traffic, Goats, Sheep, Chickens and a Trek

- Like Gods, Like Humans? Or, Like Humans, Like Gods? Or, Like…F*cked up?

- Ever Wondered Why We Have Such Warped Structures in Nepal? Here’s Part of The History Responsible For That has more on the communal landholding system of Kipat and what the Shah, hill so-called High Caste Hindu rulers did to it.

- So Your Ancestor is a Casteist? The Standard Responses to the Question & Their Alternatives

- How To Rule 101: Khas-Arya Nepali Eshtyle