One of the many consequences of the abysmally poor quality of education system and poor level of education of the population in Nepal is a significantly high percentage of population lacking in knowledge and understanding of the casteist history of the country and its legacy.

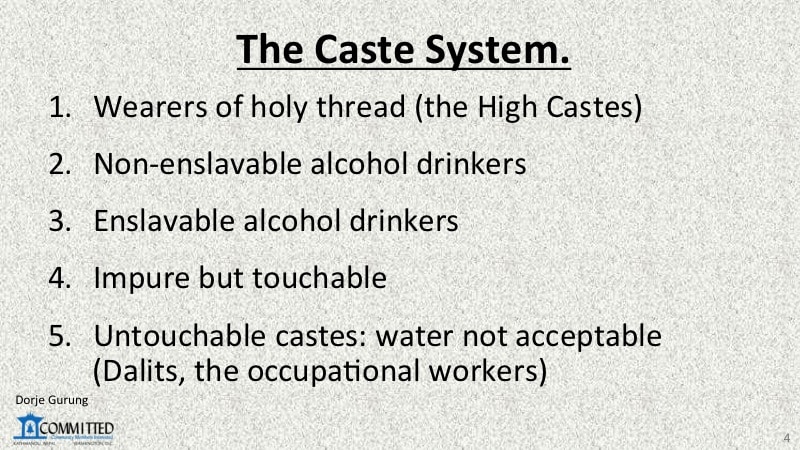

At the individual levels, you can see its legacy in the way Nepalis display casteism–big and small, overt and covert–in their beliefs, in their language, in their behaviors, and in their practices, such as marrying within one’s own ethnicity or caste etc. How many question them and how often? I will go as far to contend that the caste system (see image below) has corrupted the minds of everyone–the only difference between individuals is likely in the ways and extent of corruption.

Who in Nepal thinks that there’s anything wrong with King Prithwi Narayan Shah’s proclamation that Nepal is a garden of four castes and thirty-six varna (“नेपाल ४ जात छात्तिष वर्णको फुलबारी हो”), for example (see below)? Likely not a significantly high percentage.

That we are ४ जात छतिस वर्णको फुलबारी means that we are unequal b/c we are NOT flowers.

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) January 11, 2021

D category (“jaat” or “varna”) a flower belongs to does NOT “affect” how it is “treated” by other flowers or d gardener. Being human, jaat/varna is USED against you!https://t.co/eRfadyDnLQ

But, of course, when it comes to individuals, there’s a pretty simple explanation behind all that.

Psychology says, no one believes or wants to believe that they are “a bad person.” Who in Nepal would want to believe and acknowledge that they could be casteist, forget are?! At the other extreme, however, are those who have been brainwashed into believing that there is no caste-based discrimination but rather a lot of social harmony in Nepali society. Consequently, many live in denial of the pernicious and insidious social system.

Regardless, one of the many legacies is caste being triggering. What it triggers and how depends on the individual, and, more importantly, on their caste. The reason, obviously again, is the casteist history of the country and its legacy, which benefited the hill so-called high caste Hindus but harmed the rest, more or less depending on their caste.

What it triggers, & how it is

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) June 8, 2020

triggering to, a hill so-called high

caste Hindu in #Nepal, on average,

is very different from a non high

caste, both in level & extent.

Reason?

Our history & it’s legacy.#CasteSystem 2/

Throughout the entire history of the country of Nepal, the non-high-castes have suffered from casteism, some more than others. Dalits have suffered the most. The Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) of 1854, which was revised only in 1963, codified and legalized the differential views and treatment of members of the population in all spheres of life based on the their caste–something that had been part of the culture of the country for a long time. Not surprisingly, that gave rise to the highly unjust and inequitable society that Nepal has always been and continues to be.

So, if you are a hill so-called high caste Hindu, when a non-high-caste is triggered by caste AND shares the reasons for it and/or its nature, the best or most appropriate thing to do is to listen. Don’t give into the temptation to go on the defensive or offensive and dictate that person’s narrative.

As has already been alluded to, what it triggers in a non-high-caste, on average, is far worse than what it does in a high caste, if it is triggering at all. What is true is that, as a high caste, you are structurally privileged and therefore you really aren’t capable of imagining why and how they would be worse in someone else.

That is NOT a comment on your intellectual ability; that’s more a comment on your lack of experience–lack of life experiences as a non-khas-Arya in Nepali society. Forget about really being able to relate to the totality of the life experiences of an average non-Khas-arya Nepali.

What it triggers in a

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) June 8, 2020

non-khas-Arya, on average, is

far worse than what it does in you.

Based on the many MANY reactions

I have seen on social media & heard

in face-to-face interactions in real life,

I have come to conclude that if you

come from a #StructurallyPrivileged … 4/

… totality of the life experiences

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) June 8, 2020

of an average non-Khas-arya

Nepali. That would be especially

true of a #Dalit, a Tamang, a Tharus,

or another Madhesi.

Nepali society is segregated,

prejudiced, & highly discriminatory,

more than we care to admit. 6/ https://t.co/dFQ87B1Wi2

(How many Khas-aryas are cognizant of, receptive to, and accommodating of the life experiences and personal stories of strife and struggles of others? How readily do Khas-aryas listen to non-Khas-aryas?)

If you are not aware of any of that, if you are not willing to concede that as possibly being the case, then you are unwittingly contributing to an already unjust and inequitable society.

(How many Khas-aryas are cognizant

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) June 8, 2020

of, receptive to, & accommodating of

d life experiences & stories of others?)

If you are not aware of any of that,

if you are not willing to concede that

as possibly being d case, then you are

contributing to an unjust & inequitable

society. 7/

To reiterate, of course, Nepali society has always been highly casteist and highly unjust and inequitable and continues to be. Just because you don’t know or believe or feel or even see it or view it to be so does not make it NOT so. That, more than anything, reveals your privilege-endowed blind spot. There is a reason for Nepal still continuing to be one of the poorest and most corrupt countries in the world!

Oh yes, Nepali society is highly

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) June 8, 2020

HIGHLY #unjust and #inequitable.

Just because you don’t know or

believe or feel or even see it to be so

does not make it NOT so. That,

more than anything, reveals your

privilege-endowed blind spot. 8/

So what can one do to make Nepali society just and equitable? What can hill so-called high caste Hindus like you do?

There is lots to do and many things you can do. BUT one thing you MUST do is to respect others as you do your own kind. That respect for others, however, won’t sprout on its own. Respect for others will only come through an understanding of them–of their language, culture, heritage, and, most importantly, of their life situation and experiences. Respect without understanding is hollow respect, as hollow as the social harmony that supposedly exists between people of different castes.

…–their language/culture/

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) June 8, 2020

heritage, & most importantly

their life situation & experiences.

Respect w/out understanding

is hollow respect, as hollow as d#SocialHarmony that supposedly

exists between people of different

castes. #Nepal #CasteSystem 10/https://t.co/RhYgYBPGjB

And how does that understanding come? How does one start sowing the seed of that understanding? By being willing to listen, and I mean that in every sense of the word. As one who is structurally privileged, you must allow others a voice to dictate their narrative.

The understanding, in addition to helping you develop respect for them, will also open up a window into their lives and their situation, leading you to empathize with and have compassion for them. Being compassionate is critical for a society to get on the path to becoming a just and equitable society. Being compassionate is something Buddha–who was “born in Nepal,” something Nepalis don’t tire of pointing out–taught anyway. You’ll then come to see them for who they are: fellow human beings on exactly the same journey we call LIFE!

… w/ & have compassion for,

— Dorje Gurung, ScD (h.c.) (@Dorje_sDooing) June 8, 2020

something Buddha–who was

“born in #Nepal,” something

Nepalis don’t tire of pointing

out–taught. You’ll then come

to see them for who they are:

fellow human beings on exactly

d same journey we call LIFE!#CasteSystem 12/end https://t.co/Ip6FpNFLBn

Of course, you can replace hill so-called high caste Hindu with any caste or ethnicity and discuss the above in light of what their beliefs, attitudes, practices, and behaviors are towards fellow Nepalis they view as “inferior,” whether according to the caste system or some other social system within their own ethnic community. Of course, as everyone in Nepal is aware, there’s gradation between ethnic groups and within the ethnicities that make up a caste.

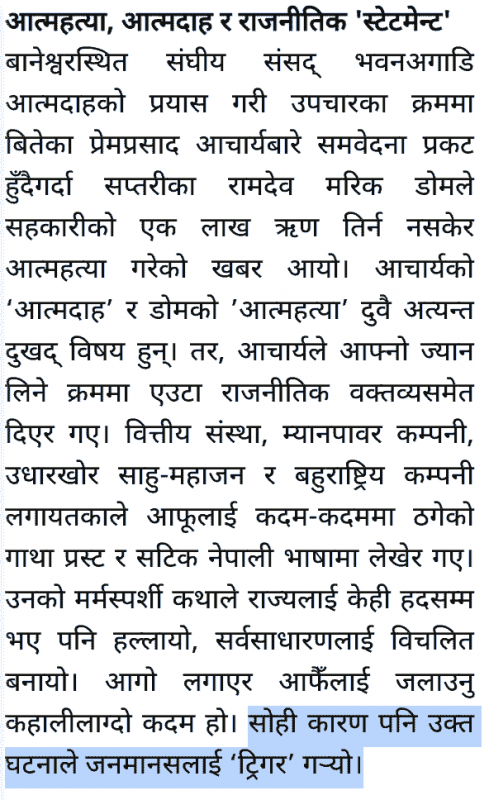

To end with a recent example…. Professor Sanjeev Uprety in his article हिंसा र शोषणको जात, लिंग वा वर्ग हुन्छ? (“Is there a caste, gender, and class of victims of violence and exploitation?”) rightly points out how a horrendously heartbreaking and unsettling incident of self-immolation by Premprasad Acharya, an entrepreneur, in front of the parliament building, triggered many (highlighted bit in the image below)–as it should!

“Suicide, Self-immolation and Political Statement

As people were grappling with the death of Premprasad Acharya following his attempt at self-immolation in front of the Parliament Building in Baneshwor [Kathmandu], news arrived of the suicide death of Ramdev Marik Dom of Saptari [in the Southern plains] caused by his inability to pay off a Rs.100K [approx. USD900] loan to a Cooperative. Both Acharya’s self-immolation death and Dom’s suicide are extremely heartbreaking. But, Acharya left behind a political statement in his suicide note. Written in clear and accurate Nepali, the story detailed all the manners in which he had been exploited by financial institutions, employment agencies, lenders, and multi-national companies at every step. His touching story shook the State some and perturbed the general population. To self-immolate is an interesting act. For that reason, the incident ‘triggered’ people.”

Obviously, there are probably a number of different reasons behind people being triggered by it in addition to the one Uprety identified. In addition to the act itself, the other contributing factor was likely the political statement, his long and detailed Facebook suicide note.

The note told the story of the constant and life-long struggles of the thirty-six-year-old Acharya! He had attempted a number of different jobs–including a four-year stint in Qatar as a Sales Manager. He had also dipped his hands in a few of different businesses as well, from travel to packaging factory to a dealer etc. But, each time, he had faced obstacles and hindrances leading him to suffer from depression and to attempt suicide “hundreds of times.” He provided minute details of pretty much everything he had faced and discovered–all the hurdles and irregularities in the rules, policies, and in the culture of doing business in the country. He actually named a whole range of businesses as well as as individuals who had either duped him or exploited him. So naturally, his story triggered a lot of people from a whole range of walks of life as each could find, in his life story, something they could relate to.

Having said that, there’s likely also differences in the way peoples belonging to different class, gender, and caste were triggered by the incident and his story.

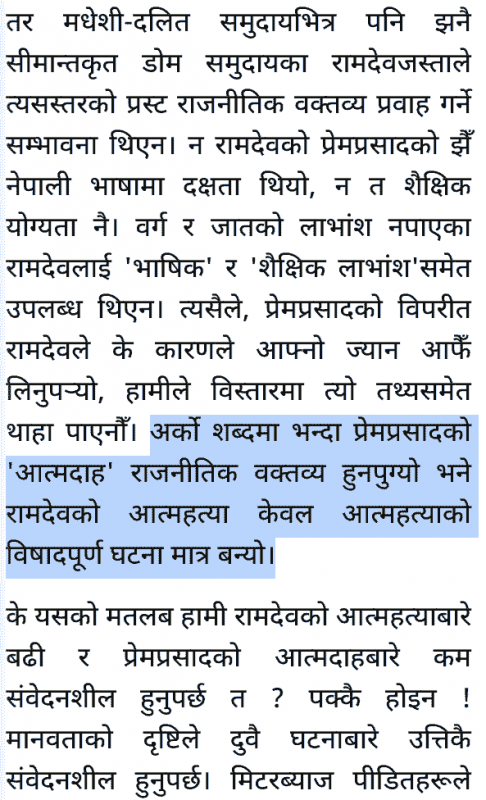

Uprety then contrasts all that to the details and circumstance of Ramdev Marik Dom’s suicide (see below) to explain why there wasn’t as much attention paid to his.

“But as a Dom, one belonging to one of the more marginalized community even within Madhes-Dalits, there was no possibility of Ramdev publishing such a well articulated political statement. Ramdev neither had the language skills Premprasad did nor did he have the academic qualifications. Not being born with any class and caste privileges, Ramdeve did not have access to opportunities to attain such language skills and educational qualifications. As a result, we don’t know all the contexts and details of why Ramdev had to take his life. In other words, Premprasad’s self-immolation became a political statement while Ramdev’s suicide just another sad incident.

“Does that mean we should be more sensitive to Ramdev’s suicide than to Prem Prasad’s self-immolation? Definitely not. Humanity requires that we should be equally sensitive to both.”

Of course, I agree wholeheartedly. The reason being that I am a humanist and therefore I place the same value to every human life, irrespective of their caste, gender, age, religious affiliation, nationality etc.

But, at the same time, the question is have we been equally sensitive? Of course NOT. We have rarely given the necessary attention to the plight of Dalits including when they were paying the ultimate price. As a society, we have NOT been paying attention to and analyzing the deaths of Dalits with the seriousness they deserve.

Returning to being triggered by self-immolation of Premprasad…representatives of the State, the media, and the general population shared their reactions to the incident. The Minister of Health and Population even visited Premprasad while he was tethering on the brink of life and death at the hospital before he, most unfortunately, succumbed to his injuries. Many, understandably and rightfully, were horrified and shaken, as I was. Many had questions, had debates, and mourned the passing openly in public forums. Ramdev’s suicide garnered nowhere near as much attention.

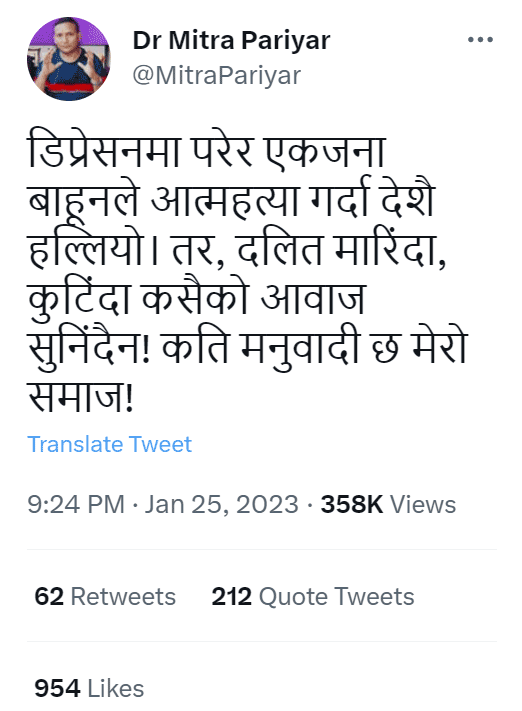

In the aftermath of the passing of the two, something else happened. Dalits were also triggered by something else altogether, namely by that disparity in the reactions to and treatment of the two deaths. That is, the double standard in the way the two deaths were being viewed and treated triggered them. Here’s one tweet which expresses that sentiment, albeit in a very direct manner without mincing his words.

“When depression drives a Bahun to kill himself, the country is shaken. But, when a Dalit is killed, beaten no one raises their voice. So inhumane is my society.”

And again why would Dalits feel that? Well, because of such disparate reactions to and treatments of suicide deaths and of many others (such as rape, violence, abuse, exploitation etc.) based on the caste of the victim for the entire casteist history of the country is why. Forget disparity in how deaths are treated, from 1854 to 1963 the law allowed for differential punishment of perpetrators of crime based on his or her caste–the worst was reserved for Dalits. That is, Dalits have been dehumanized throughout and, therefore, the life of a Dalit valued the least among all castes. We are still living through the legacy of that.

Karuna Devkota writing in Himalkhabar about Nepali society’s tendency to neglect the plight of Dalit females, towards the end raises a number of questions about the impact on their psyche of growing up in such a society. She rightly concludes, and I quote:

“हामी यस्ता प्रश्नबारे सोच्ने र समाधान खोज्ने आवश्यकतासम्म ठान्दैनौं। किनकि हामी अझै पनि दलितलाई समाजको अङ्ग स्विकार्न हिचकिचाउँछौं।”

(“We think it’s unnecessary to think about such questions and find solutions to them because we still hesitate to accept Dalits as members of our society.”)

Consequently, Dalits likely suffer from generational trauma. In other words, Dalits likely also have trauma responses to–what to them appears as–such blatant evidences of exclusion AND disregard for the lives of their kind. Members of other castes with the exception of the so-called high caste likely do too but, again, nowhere near as much or as deeply.

So, to reiterate, caste can be considerably more triggering to Dalits than to others. What’s more, there’s likely a gradation in the level to which members of the other four castes are triggered by caste! Caste likely triggers the hill so-called high caste Hindus the least in comparison, if at all.

BUT what percentage of Nepalis are aware of any or all that, or recognize any or all of that?! (To as poorly educated a population as the Nepalis, what’s generational trauma anyway?) Forget acknowledge them. And those are yet some additional major issues with this deeply flawed Nepali society.

Having said that, to reiterate the most important point, when members of a caste other than a so-called high caste are triggered or when a member of a caste that to you is “inferior” are triggered AND share their experience, listen, ask for details and try to get a deeper understanding. That’s the best thing you can do to contribute towards getting this society on a path to becoming just and equitable.

What do you think?