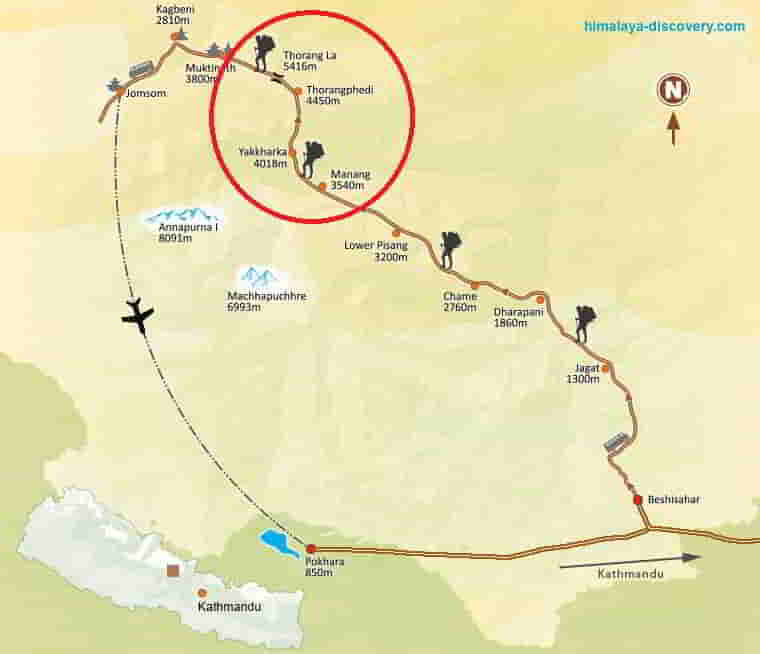

Tears streaking down my face, completely in awe of the expansive and grand vista of the parts of the other-worldly highland desert of Mustang I beheld in front of me, stretching before me from literally under my feet, topped off by the Dhaulagiri mountain range in the far off distance, the likes of which I had never seen before — an overwhelming feeling of relief and also of stupidity had overcome me. Half-way down on the Mustang side of Thorang La Pass (see circled part in the image below), I had exerted tremendous effort to get there only to discover that the reason for doing so were misguided. The date was October 11; the year, 1997.

Source: Annapurna Circuit Trek 12 Days Itinerary.

“How did I not and how could I not feel connected to — and believe that I was not an intimate part of — this land I stood on?! How did I not and how could I not be an inalienable part — as well as a product — of this incredible land?! How was it even possible that I questioned that and fought a potential altitude sickness just to realize that?!” I remembered asking myself, I remembered thinking.

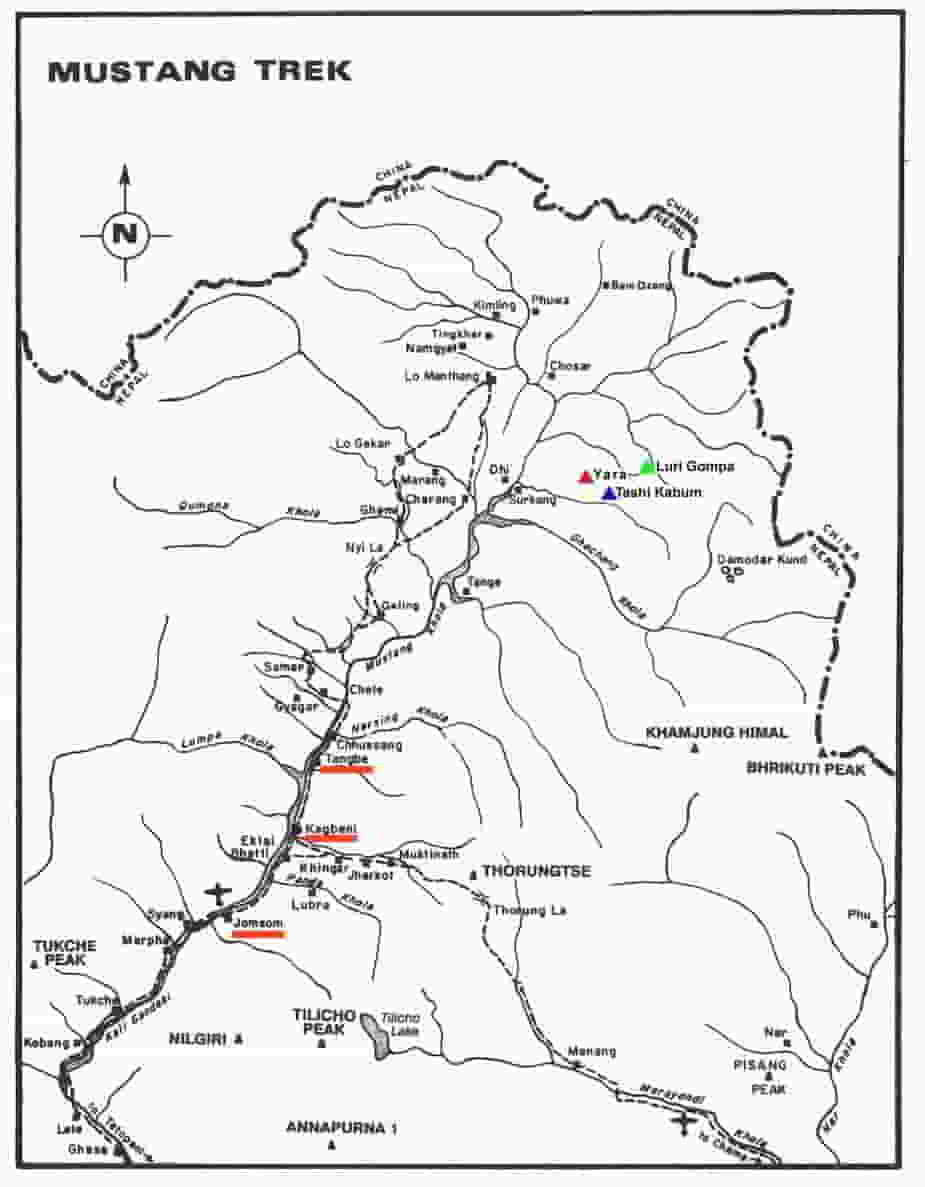

I had gone on a trek of the Annapurna Circuit to reconnect with elements of my heritage, my roots. The story of my people — the Tangbetanis, ethnic Tibetans from the village of Tangbe (one of the three underlined in the image below) in Mustang District — were that we had originally come from a village in Manang District. Some remains of the village still stood, apparently. According to one source, our ancestors had been forced out of the village, forced to head out West beyond the mountains, over the Thorang La, and had settled in Tangbe .

Being, at least at the time I was growing up, from such a remote part of Nepal and ethnic Tibetan — Bhote in Nepal, which has negative connotations — had driven me to strive to “escape” from the country for lack of a sense of real belonging to Nepali society, among others. The abyssmaly poor formal education about the country, its history, society, and people, instituted by the autocratic Shah rulers and their cronies, and the informal social education system, shaped heavily by the caste system, had made an impact on me, a detrimental impact, some that I hadn’t even been aware of. It had brainwashed me into believing that, the civilization in Mustang District I was a product of, were “backward,” for example. But I had come to resent the low social position my people and I had been relegated to based on the caste system.

Going completely against the grain and societal expectations, I had been dead set on getting further education. But because of my lowly caste-based social status and other reasons, I had been convinced that I wouldn’t amount to much were I to seek advanced degrees in the country and try to make something of myself. I had been convinced that the society’s views of and the very low expectations of me would hold me back.

To liberate myself from that, I had been steadfastly driven, from when I had been a fifth grader, to do everything I could to make it to the US for further studies — to improve my chances of becoming someone other than that which Nepali society had said I could be. Notably, to become someone MORE than that which Nepali people holding caste-based beliefs about and attitudes towards people like me had said or thought or believed I would.

Having succeeded in my quest to “escape”, by the Summer of 1997 I had lived abroad for ten years — first as a student, and then as a teacher. I had been educated in three and worked in also three countries. That summer, I had returned to Nepal for a year-long interlude between my professional teaching career and yet another academic pursuit — a teaching degree — also abroad.

Returning after a decade abroad, not surprisingly, had made me question further who and what I was and who and what I had become etc., driving me to take that long trek around Annapurna Circuit in the Fall of 1997. One reason had been to see the remains of our original ancestral village in Manang. The other to walk on the trails my ancestors would have likely been on on their way to Mustang — including the Thorang La Pass — to trace my roots and connection to the land, to our land, to my land.

The hike over the pass starting at 2 am on October 11 from Thorang Phedi at 4450 m (see image of Annapurna Circuit) had been an arduous one. (Trekkers started the cross-over so early in the morning to avoid the harsh and high speed early morning winds on the other side.) As a matter of fact, from around 5000 meters, I had suffered from the altitude and seriously considered abandoning it and returning to Manang. But somehow I had managed to make it to the Pass, at an altitude of 5416 m.

But once there, fully aware that my struggles had been due to the altitude, leaving the others behind, I basically raced down the other side — literally raced — until I had gotten half-way down. There I had stopped, overcome with an overwhelming feeling of stupidity at my attempting the hike and relief at having not suffered from altitude sickness while at the same being total awed by the scenery I beheld, all of which had made me cry silently!

Fast-forward to early 2012, when I finally began contemplating, seriously, returning to Nepal, almost a decade and a half had passed. I had been educated in yet another country and worked in six more countries and traveled in a couple of dozen others. In other words, a lot had happened.

In addition to all the reasons for returning to Nepal, described in other blog posts in this series, another had been to see if Nepal was (still) home. That connection I felt for the land one beautiful October morning back in 1997, is that still there and could I build on it?

Of course, I wasn’t so naïve to think and believe that I had sufficient understanding of the country and people and life there. I did still feel an intimate connection to them too, in addition to the highland desert of Mustang, and I did still feel I could relate to my fellow Nepalis…sufficiently. But still, of that connection I felt, thought, believed, I had with them, or had maintained, were they real?

Years of education, professional experience, and travels had led to my deeply valuing kindness, honesty, integrity, compassion, peace, justice, humanity, non-violence, knowledge etc. All the years I had been abroad, I had always believed that the Nepali people were also kind, honest, tolerant, considerate, and highly accommodating etc. etc. But the question was, “Were they…still?”

“If none of them were true and if changes in the circumstances demanded that I make Nepal my home, could I?” was yet another question. In all the years living mostly abroad since 1988, I, obviously, hadn’t made a home of — or in — any country.

Sure, the country certainly had its share of problems! But I had come to believe, for example, that it was nowhere near as corrupt as Azerbaijan, and the society nowhere near as conservative as the ones in the Central Asian Republics.

(Little did I know that after a few years, I would discover, firstly, that Nepal was incredibly more corrupt and Nepalis to be incredibly more closed and inward-looking than I had ever believed or imagined.)

Finally, as for making Nepal my home, I had had this long standing belief in Nepal as one of the best places to raise children. Even though I had wanted children of my own since a teenager, I still didn’t have any. I still nurtured that dream however. “Could I have children in Nepal and raise them there and thus create a home of my own there?” was another question.

(Little did I know that after a number of years, I would come to decide that Nepal is actually a horrible place to raise children, especially female children.)

In short, it wasn’t just enough to feel the connection to and hold the beliefs I did about the people, country, and society, of course. I needed to find out for certain, for myself. The only way to do that was to return and live — and be — among the people.

What I was certain of was that life and everything else in the country promised a great deal of uncertainty and challenges, not unlike moving to a completely new country, something I had done regularly for almost 25 years! But this move entrailed repatriation challenges, accompanied by challenges inherent in a career change — I was planning to quit teaching and do something else.

And keeping with the kind of life I had had all my adult life until then, the prospect of new challenges was another draw for turning down the February 2013 job offer and returning to Nepal.

(Little did I know, just some years later, I would feel completely disoriented, disconnected, dislocated, and disenchanted, rendering my feeling of connection to the land I had experienced in 1997 a distant distant memory.)

What do you think?

Wherever you are can become your home, if you join the society and help it try to solve its problems until the day you die. Most of such problems cannot be solved forever, but little steps can be accomplished, and your simply being there and being a little light in the darkness for others makes a difference that can be bigger than you ever know. The investment you make in “home” is yourself and your decision to make that difference.